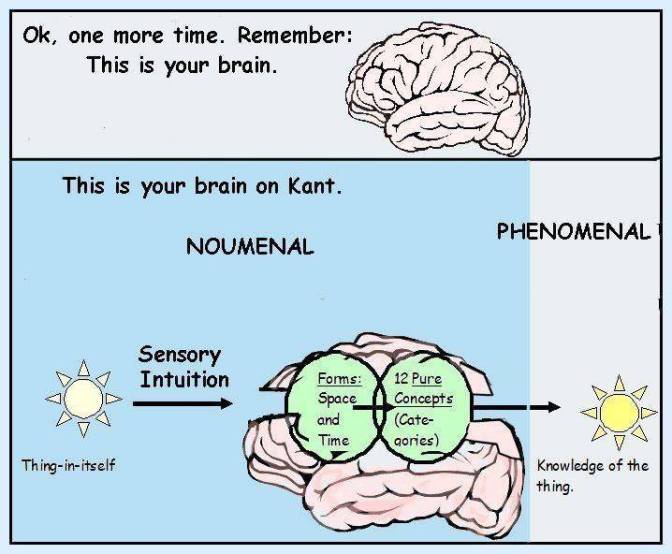

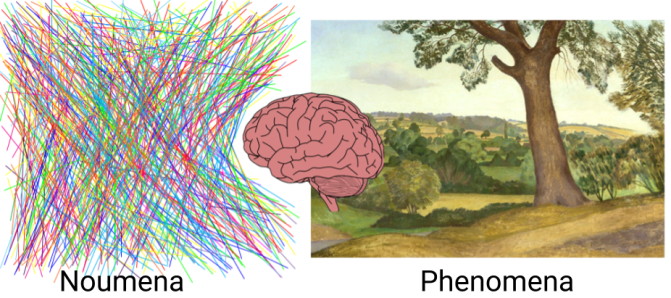

What sound does a tree falling in a forest make if no one is around to hear it? Answer: none, because sound is a phenomenon that requires a subject to perceive it. A lonely falling tree doesn’t emit sound, but waves of air pressure that could potentially become sound if a subject were there to perceive (receive) them. (Given, of course, that the subject if capable of processing acoustic signals.) Immanuel Kant differentiated between the world-as-it-is, and the world-as-it-appears in his monumental Critique of Pure Reason. He called the former, the noumena, and the latter, the phenomena. In the falling tree example, the oscillations of air pressure are the noumena, whereas the sound is the phenomenon.

Kant argued extensively in his Critique that there’s not too much that we can say about the noumenal world, because even if sound is a series of waves of air pressure, these are how they appear to us. (Hard to grasp, but true.) However, we know that the brain is doing a pretty good job representing and organizing the signals coming from the noumenal world in a coherent and useful way, because if the brain didn’t adequately “tell” us -for instance- that there is a ditch ahead in the road, then we would have very limited survival chances. Having said that, there is a lot that the brain “extracts” or “deduces” from an incoming signal that we usually take for granted, but it is only when we aim to build systems that think for themselves (think of artificial general intelligence, AGI) or learn about a brain disease with unfortunate and rare consequences that we marvel about the sophisticated processes and algorithms that the 3 lbs. organ contained in our skulls perform in a fraction of a second.

What is the knowledge that we gain when we hear something, say the voice of a person? We know the approximate distance between us and the speaker, as well as their location in space (north, south, etc.) relative to ourselves (that is, echolocation). We also know, in an upper level of abstraction, the intention of the speaker, their emotional situation, and much more. An acoustic signal doesn’t contain this information, rather our brain extracts it from the signal. In the same sense, a visual signal doesn’t include information about distance, texture, form and content, etc. about the objects in the world “out there”. The brain learns to extract this kind of information from the signals coming through the senses. Some of this learning might come for free via the genetic code, and the rest is learned via culture. In the latter case think of written language, and how some characters in a piece of paper carry meaning to those who know the particular language in which the characters were written. In the former case, it seems that we (along with possibly the entire animal kingdom) are wired to extract information regarding time and space. (Although some species might develop more sophisticated notions of them than others.) And here we return to Kant, who conceived time and space as a priori notions, in a way that they might be fundamental in order for the mind to construct the rest of its conceptual apparatus. My guess is that a newborn spends the first months of their lives improving their notions of time and space, and that their motor “babbling” helps them for this purpose.

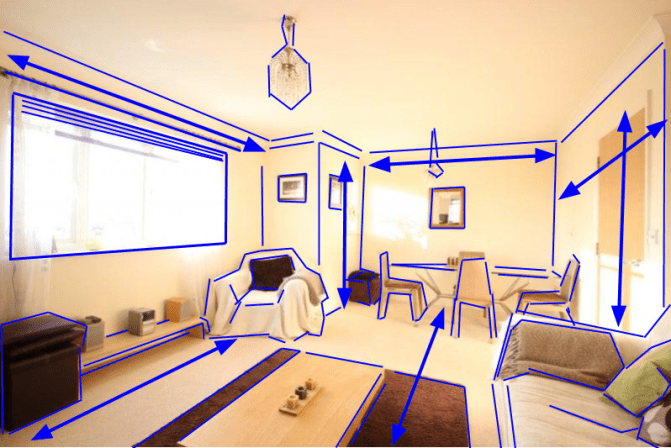

What do our brains deduce from incoming visual stimuli? Consider for instance the image below. It looks like an average living room, but at different levels of abstraction our brain is able to extract different pieces of information.

In the most basic level, our brain is able to “tell” us information about the objects’ geometry and their distance to us, as well as information about their texture. In an upper level, we not only know how to name the objects comprising the scene, but also we know about their functions and uses, as well as their mutual relationships, and if there were written characters somewhere in the scene, we might be able to understand their meaning provided we know the language in which they were written.

We see these objects as information. That’s all that there is. A white sofa in the corner of the room is the information about a white object with such-and-such geometry in a so-and-so spatial disposition in our own frame of reference. That is, when we see an image like the one above what we really see is information, for instance, that there are X number of walls in front of us, that they are at Y distance from us, that they are of color Z, that the ceiling is of height A, that there are B number of lamps hanging from the ceiling, that there is a coffee table at distance C, and so on. However, I’m not saying that the brain extracts this information with precision inside the framework of a specific measure system, in other words, when I say that the brain deduces “distance” in a visual scene, I’m not saying that it does so in a precise way, as if it said for instance that the table is “3 meters” away from us. Rather it is saying that the object is “at a distance” from us.

Similarly, whenever we meet someone for whom we feel sexual attraction, our brain is extracting information from visual stimuli that is relevant for the purposes of mating and choosing a partner that will maximize the survival chances of our potential offspring.

Philosophers of mind like David Chalmers would like to see insurmountable and obscure problems in the way that objects affecting our perception look. He coined the expression the hard problem of consciousness to capture the idea that there is something special and mysterious about the fact that -say- the color white looks the way it does. He does so thinking that perhaps objects in our “consciousness” should rather look like the green arcane characters from the movie The Matrix, or like some weird and even more arcane assembly code language of the mind, and because these objects actually don’t look anything like that (sofas look like sofas rather than green arcane characters), then there is something mysterious (and hard) about this consciousness thing. What we call the act of seeing, or hearing, or any other act of perception, is just the presentation of spatial (or acoustic, etc.) information extracted from a signal. (Presentation from who to whom -the reader might be wondering- is the topic of another upcoming essay.)

In my opinion, questions such as “why does the color white look the way it looks?” (even if you and I don’t perceive the same color that we agree in calling “white”) fall in the same category as questions such as “why does the hydrogen atom possess only one proton?” or “why are there atoms in the first place?”, “why are they comprised of protons, electrons, etc.?”. These teleological (or “why”) questions are beyond our grasp, and do not contribute anything to our understanding of nature. Rather, we should substitute them with “how” questions, such as “how is it that the brain extracts spatial information from waves of air pressure?”.

As mentioned earlier, the brain learns to extract/deduce information contained in an incoming signal. For this to occur, the brain must learn the concept of the thing to be extracted from the signal prior to its extraction. For us to be able to deduce something like “distance” from an incoming visual stimulus, we need to possess the notion of “distance” even if we are not -yet- able to name it. In other words, for all the things that we might extract from an incoming signal, we possess a concept even if we cannot name it in our language. And for all the things that we might be able to extract in the future, first we need to learn them as a concept intentionally or non-intentionally, or using cautiously the C-word: consciously or unconsciously.

Consider the case when you hear a voice. Your brain extracts information such as distance, ownership of the voice, orientation, intention, meaning of what is being said, etc. from an acoustic signal. It is because you have concepts such as distance, speaker, location, etc. that you are able to extract such information. (As mentioned before, not having a name how to call such concepts doesn’t prevent your brain from extracting them from stimuli.) Now, imagine that you have a particular and rare disease by which you are not able to distinguish one speaker from another, that is to say that any human voice will sound the same to you. It is as if you understood speech from the (undifferentiated) subtitles shown in a movie. In such an unfortunate situation, you would come to appreciate the fact that information regarding the speaker is not contained in the signal but rather it is deduced from it.

Such a disease is known as phonagnosia. People affected by this disease suffer an impairment of voice discrimination abilities without suffering comprehension deficits. Now imagine a disease in which you are not able to deduce the distance from an acoustic signal. In such a situation, all sounds will sound as coming from the same source. The signal couldn’t care less for your inability to discriminate distances, speakers, and so on. It does not contain any of those pieces of information. It is your brain who extracts it. The question is then, could the signal carry more information than what we are able to extract? We know that we can learn to extract information that previously we couldn’t extract. For instance, a child might not be able to distinguish the emotional situation of two people having a dialogue, but as she grows she will improve this skill by social interaction and/or explicit learning. The fact that there is people better than others at distinguishing (deducing/extracting) emotional content from the interaction with people has led us to consider the existence of something like emotional intelligence. Could it be that some forms of autistic spectrum disorders arise from the brain’s incapacity to extract specific information from its incoming stimuli?

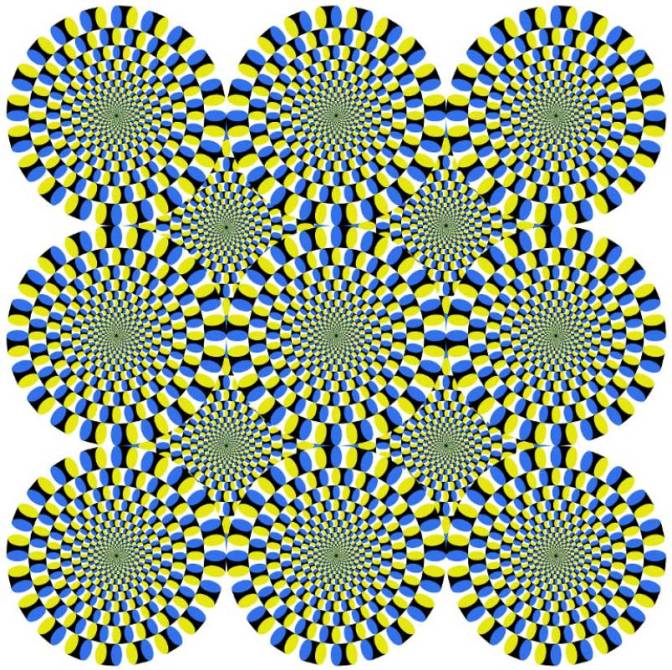

Now, let’s consider convolutional neural networks, better known as convnets, which as of today comprise the most successful methods for computer vision. Are convnets extracting anything from their incoming visual signal? Do they know anything about distance, texture, content, subject, etc. when they “look” at an image? They don’t. They just learn statistical regularities among the vast data used to train them. They might be able to tell you whether a particular picture corresponds to a cat or a dog, but they cannot tell you where is the cat (or the dog) in the picture simply because it cannot tell foreground from background. It simply lacks those concepts. What they are actually telling you is that there is a cat (or a dog) in a particular photograph, but not where in the picture the animal is located. Because of the fact that convnets only learn statistical regularities in data, they are susceptible to adversarial attacks in which -for instance- flipping the image of a learned object in a picture, makes the convnet return a nonsensical prediction. It’s only when convnets learn to extract conceptual information from its signal that they will be more robust to this kind of attacks. On a final note, we human beings are not completely invulnerable to adversarial attacks of some sort. We call them visual illusions, and for instance, they trick our brain by making it extract motion information when actually there is none of it.