Let’s start with thought. That act of sequence generation, which it is most of the time considered the pinnacle of mental endeavours and abstract reasoning. Thinking relies on a generative and voluntary process of pattern formation. Unlike perception, which is a passive act, thinking is an active process in which the mind creates sequences1.

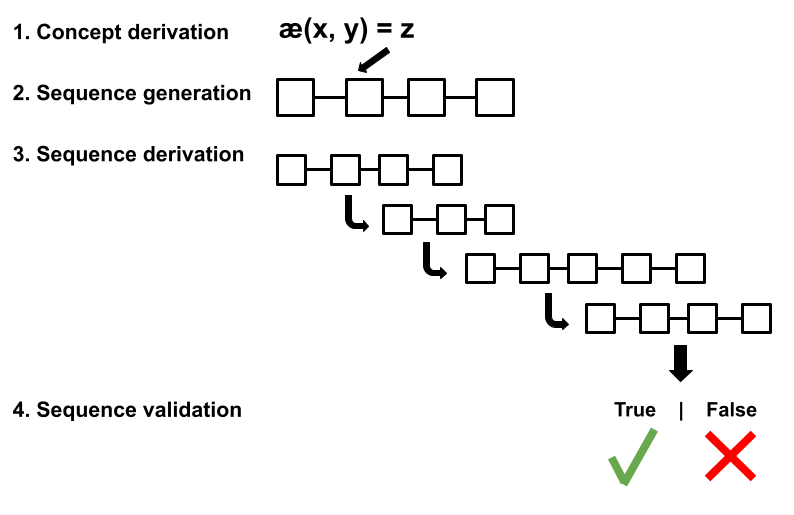

Sequences of what? Broadly speaking, these are sequences of concepts. However, the situation is a bit more complex than that. Each of the items comprising a thought is declined, derived. Each item starts from a concept in a raw, neutral form, but then it is declined according to the purpose of the idea that needs to be conveyed. Such a process follows a type of conceptual algebra that needs further investigation. We might start with concept x; however, if the idea we would like to convey refers to x as the possession of another concept y, then we decline x accordingly. For instance, in Nahuatl -the language of the ancient Mexicas that is still spoken by some people in Mexico- the concept of “house” is represented by the word “calli”; whereas the concept of “over/in top of” is represented by the declination “-pan”, such that the combination of such concepts (“in top of the house”) results in the word “calpan”, that is, æ(“calli”, “in top of”) = “calpan”. This type of derivations are the elements comprising a thought.

Thoughts are comprised of concepts. Derived concepts that is. But what do we think about? What do we usually make thoughts for? What are the kind of things that this generative process is interested in? We build thoughts about the past, present, and future. Thinking about the past is remembering. Thinking about the future is speculating, it is thinking about hypothetical situations in order to assess their plausibility. Thinking about the present is making opinions or reflecting upon something. Thinking about the future also serves the purpose of planning and plotting. One of the arguments I would like to put forward is that thought is essential for intelligence; or rather evocation and the capacity for speculation, but more on that later.

Where is thought created in the brain? Before diving into that question, let’s first consider two main functions of the mind/brain (here I am not going to formally differentiate between the two). These functions are: perception and evocation.

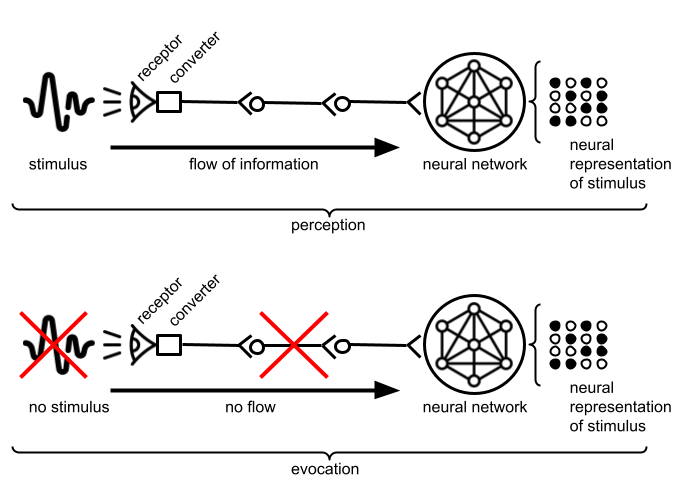

In simple terms, perception is the act of receiving a stimulus from the senses and represent it by the activation of neurons in the brain. Evocation refers to the reproduction of a representation in the brain in the absence of a stimulus.

Evocation is a generative process whereas perception is a discriminative process. Evocation can be voluntary or involuntary. (The latter case might emerge as a result of a perception or a thought triggering an evocation of some nature.) A perceptual system is a neural system responsible for processing the stimuli incoming from a particular sense. For instance, the visual system is the perceptual system responsible for processing stimuli coming from the eyes.

Thought is thus produced in the auditory perceptual system, that is, the system that handles sound, spoken language and its perception. This, at least, is the kind of thought that we are able to talk about, the kind of thought that follows a particular set of rules from a language’s grammar and syntactical representation. Neurobiology tells us that there are 2 main areas devoted to language in the brain: one devoted to language understanding (known as Wernicke’s area), and another devoted to language production (known as Broca’s area). The kind of thought that follows the rules of language stems from this latter area.

Here I am making the distinction between 2 types of thought: one that follows the rules of our mother tongue and which is colloquially described as an “inner dialogue”; and another that is not constrained by the rules of language and it comprises concepts in a purer -yet, derived- form. I call the former grammatical thought and the latter symbolic -or primitive– thought. Symbolic thought is the precursor of grammatical thought, and it is only when we use the words attached to each concept comprising the symbolic thought that it becomes a grammatical thought, and thus we are able to talk about it.

What about people who are unable to perform speech? These people still think symbolically, and then the languatization is executed on the system that they use to communicate. For instance, it is well documented that people that use sign language “think” in terms of hand gestures.

Thought then is a sequence of derived concepts that occur in time. A derived concept is the activation of a neuron cell assembly in the brain. Thought produces other thoughts, or results in another type of output in the body such as emotion or motor action.

The mind possesses an ability to generate speculative thoughts, that is, thoughts that do not reflect reality in its entirety but rather contain some hypothetical aspects of it. With speculative thought the mind is testing “what-if” scenarios which trigger the creation of other thoughts that serve to follow the consequences of the initial speculative thought.

Intelligence is based on such a principle, that is, in the capacity of the mind to generate hypothetical thoughts and go through their consequences. However, the process of taking a thought to their ultimate consequences based on the interaction of their constituents is a process that requires further study. That process is reason.

Reason is used to confirm the plausibility or validity of a given thought. One thing is, for instance, to produce a thought such as “all bachelors are unmarried”, and yet another to verify its plausibility. That is another act which is based on studying, pondering, the components of the thought and their relationships. Reason can act upon a single thought as in the example above, or upon a series of them, as in the classic syllogism: “All men are mortal/ Socrates is a man/ Thus, Socrates is mortal”.

Evocation in the visual system is called imagination. Thought is one type of evocation that occurs in the auditory system. But this is a very particular type of evocation, because this one does not rely on memory as it would be if we were to remember that someone has said in the past. There are 2 types of evocation: one that relies on memory and another that is purely generative. When you remember the face of your mother, you evoke her based on memory. When you imagine a Pegasus with red wings flying over New York City, you evoke it without relying entirely2 on episodic memory. Thought is based on this latter type of evocation.

Finally, thought is produced and listened to almost immediately by the subject thinking it. This, therefore, reflects the connectivity that exists between Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas.

[1] The brain produces patterns, that is sequences of activations, all the time and in every subsystem. Movement, as in walking, is a type of sequence that is generated in the motor cortex and then broadcasted to the limbs.

[2] Because you still need to remember, that is evoke from memory, the images of New York City, horses, and wings; and then put all of that in a mental mix.