I have reached a point where the various social dilemmas (problems of my social life) and intellectual dilemmas (problems of my professional life) could be solved by solving one and the same question. I thought, in my university years, that the study of artificial intelligence (AI) had tacitly led me into the realms of philosophy to answer a question about human thought and its dynamics. Now, years later, different situations have led me to think that the same answer, to such a question about thought, would help me to answer questions of a different nature to the fundamental objective of AI, to wit, questions of ethics, aesthetics, and theodicy, among others. Why is this so? Simply because man (as species) is the protagonist of all these questions: man and in particular their thoughts. And it is their thoughts that interest us in this enquiry. At the end of the 17th century, a similar meditation motivated the English philosopher John Locke to investigate the ideas that make up human understanding, resulting in the publication of his magnificent Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Although this work was a major breakthrough in epistemology, today we do not feel that it, nor the works of the philosophers who followed, provide a definitive answer to the questions about the human mind. Not only that, but many of these investigations did not take into account other aspects of the human mind that interest us today, such as learning and the mechanisms of memory. Today we could not be satisfied with a theory that would explain learning purely intellectual subjects (e.g. learning a language, playing chess or go) and leave out learning those subjects that at first sight are more physical than intellectual (e.g. learning to skate or to play a musical instrument). A theory that speaks of human intelligence (and therefore of learning insofar as the latter is a condition of the former) must speak of it in all its manifestations, in all its trappings and in all its flavours.

The question of intelligence, at least that which can be verbalised, led me to wonder about thought, although we might well ask whether thought is essential to the development of intelligence. An issue that can be reduced to the answering the following questions: Is there a manifestation of Intelligence in which those objects of the mind called thoughts are not involved? What has thought got to do with intelligence?

Let us consider the following examples that can be taken as manifestations of intelligence, and see whether or not there are thoughts involved.

- Situation 1. Cosmo plans to buy an object X through an advertisement published in the newspaper, but as he is somewhat suspicious he does not want to go to the place of purchase without first meeting, at least visually, the seller. Cosmo devises the following solution: he proposes to meet the seller in a crowded place and to identify each other by their clothes; only that Cosmo plans to dress differently from what was agreed, and therefore he would be able to identify the seller without the seller identifying him first.

- Problem: Avoid a possible mugging.

- Solution: Get to know the seller before Cosmo introduces himself as the buyer.

- Thoughts involved: “It may be that whoever posted the advertisement intends to mug the buyer”, “It is through a person’s physical appearance that their habits and intentions are revealed”, “It may be that at the meeting place, the alleged seller is accompanied by his group of accomplices if mugging is the real intention”, “The alleged seller is unlikely to commit a robbery in a crowded place if robbing is his real intention”, “The buyer and the seller are two strangers who must establish an identification mechanism between them to identify each other when the rendezvous takes place”, “If one of the two strangers does not respect the dress code, the other cannot identify him, while he can be identified”, “By knowing what the other is wearing, it is possible to judge him visually and to know if others are accompanying him”, “If there is nothing wrong with the seller, one can always approach him on the grounds that it was not possible to respect the dress code”.

- Situation 2: Prince Hamlet is sent to England along with Guildenstern and Rosenkrantz, who act as his guardians and who also have explicit orders to deliver a letter to the King of England with the Danish royal seal. The letter calls for Hamlet’s immediate execution. However, during the voyage, the prince manages to read the dire letter, and thus anticipate the events. Hamlet resolves to rewrite the letter and seal it with the seal of his late father, the King of Denmark. The amended letter requests the King of England to immediately execute none other than Guildenstern and Rosenkrantz themselves, putting the Danish prince in safety.

- Problem: Avoid execution.

- Solution: Alter the execution orders.

- Thoughts involved: “If the letter to be delivered to the King disappears, they will suspect of me”, “I can get rid of my custodians by changing the subject of the execution for themselves”, “The letter must have the royal seal to be considered legitimate”, “The late King’s seal may do”.

- Situation 3: Edmond Dantès is imprisoned in Château d’If: a fortress fitted out to serve as a prison and located on one of the islands of the Frioul archipelago. Looks like his fate was to spend the rest of his days locked up in a small cell, until he met Abbé Faría, with whom he planned to escape by digging a tunnel outside the prison. By an ill turn of chance, the abbé is crushed to death by the tunnel he himself dug, putting an end to Dantès’ hopes of escape. When the prison guards realise that the abbé is dead, they decide to throw his remains into the sea. Dantès glimpses the possibility of escaping from prison by taking the place of the corpse.

- Problem: Escape from Château d’If

- Solution: Take the place of a corpse.

- Thoughts involved: “Only dead can one leave Château d’If”, “The remains of Abbé Faría will be thrown out of Château d’If”, “By impersonating the dead man I will be able to get out of Château d’If”.

- Situation 4: To end a war that has lasted 10 years, the Greeks decide to take the city of Troy from within, since the city walls are impregnable. To this end, the wily Odysseus proposed to build a huge hollow wooden horse, so that the best Greek warriors would be hidden inside. The plan was that the Trojans would be take the wooden horse as a gift to make peace with the Greeks, and once the horse was brought into the city, the soldiers inside would open the gates at nightfall to allow the Greek army to enter.

- Problem: To take the city of Troy.

- Solution: Enter the city hidden inside the statue of a horse, and open the city gates to the Achaean army.

- Thoughts involved: “The city of Troy cannot be taken through its walls”, “If one of the Achaeans could enter the city, he would open the gates to the army”, “An artefact can be built where a group of Greek warriors can be hidden”, “If the artefact looks like an offering to our enemies it is very likely that they will bring it into their city”, “The offering can be in the shape of a horse, and by its beauty it would thoroughly conceal its true intention”.

- Situation 5: There is a class of puzzles that involve separating one piece from another, and are usually constructed simply of wire, and thus, they are known as wire-puzzles. The most popular of these puzzles is the two-nail puzzle, which involves separating two twisted nails that are seemingly inseparable by force, but not by manual dexterity. Such puzzles are more often solved by manual skill than by intellectual skill, that is, very seldom does the solver sits down and makes a thorough -intellectual- analysis of the parts that make up the puzzle, and where each stands in relation to the puzzle as a whole. (Perhaps the same can be said of traditional puzzles.)

- Problem: Separate the two nails.

- Solution: Hold one of them in such a way that, given its crookedness, it simulates the shape of the letter b. Pass the other nail through the only opening that appears to measure a right angle (the one formed by the two ends of the nail when the twist of the nail is taken into account).

- Thoughts involved: There appears to be not a single one. It could be that thoughts emerge as the puzzle is attempted to be solved.

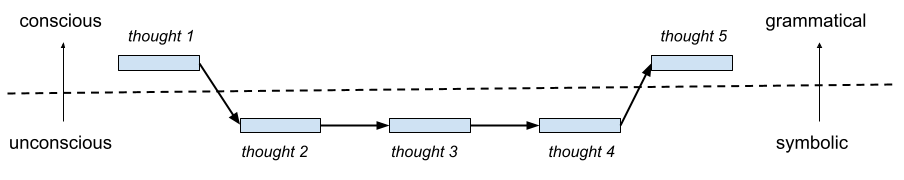

In the above situations, except perhaps Situation 5, some thoughts can be listed, which develop the solution to the specific problem. These thoughts can occur in an individual or in a group of individuals gathered around the same question. They can also occur in an explicit grammatical form as described in each section (e.g. as in the thought “Only dead can one leave Château d’If”, which is a correct sentence in English) or they can occur without a grammatical form in its purest or symbolic form. What I mean is that thought does not necessarily occur following a linguistic structure, in the form of a dialogue that a subject speaks to herself. Rather, thought also occurs in a form that does not follow the rules of a particular language, but in a more general way that contains it, and evidently precedes it evolutionarily. Thought, which we define as a dialogue that a subject speaks to herself, can be called grammatical thought, while thought, which is more general and is the basis of grammatical thought can be called symbolic or primitive thought. A question that remains open is whether these thoughts are responsible for phenomena such as intelligence, imagination and intuition. For the time being, it is enough to know that thought (in the two modalities just described) is a necessary condition in one type of intelligent behaviour (that which is apparently completely intellectual); whereas in another, it plays a secondary role or moves in a complete different direction (this is the case of problems that are of a physical rather than an intellectual nature; e.g., solving a wire-puzzle or learning to play the guitar).

One thing that can be observed in all the Situations described above is the existence of a problem to be solved. It would seem that some people forget that intelligence is a concept that is applied when there is a problem to be solved. “Intelligent” is an adjective that should be used to qualify an action that aims to solve a problem. This occurs when an action stands out from other possible actions with the same goal. For example, in Situation 3, Edmond Dantès and the Abbé Faría were attempting a solution to the problem of escaping from Château d’If (the one that they considered the best of all), before the latter was surprised by death. Thus, there is not a single action in response to a problem; and the process of proposing a solution to a problem, or a series of them, seems to be mediated by psychological processes such as imagination and experience. Imagination plays the role of creating hypothetical situations in which a supposed solution is tested, whereas experience corrects or endorses the product of imagination. Therefore, if AI aims to create systems that are capable of devising intelligent solutions to given problems, then it should consider the role that thought plays in human intelligence.

Above I mentioned that in certain problem-solving scenarios, it looks like we can find the presence of thoughts that relate to the problem at hand. These work as a basis or stepping stone that leads to the solution of a problem. They act as proposals to the solution of the problem that we try to solve.

Most of the time, we cannot “perceive” these thoughts and we might be aware only of the final thought were the solution is laid out. However, the terms “perceive” and “aware” should already suggest the nature of the thoughts involved in problem-solving. Psychologists like to talk about conscious and unconscious behaviour when referring to actions that we are aware and actions that we are not aware of, respectively. Here, I consider the similar distinction when talking about thoughts, which by the way are precursors of behaviour.

“Conscious” and “unconscious” are properties that also refer to thoughts. In other words, we talk about thoughts that we are aware of, and thoughts that we are unaware of. I claim that although it seems that there are no thoughts emerging during the solution of a problem, they do however occur but in an unconscious fashion.

One question that we might ask is what is the relationship between being aware of a thought and being capable of talking about the thought. It seems that if we are able to talk a thought then we are conscious about it. In other words: it seems that grammatical thoughts are all conscious thoughts, whereas symbolic thoughts can be conscious or unconscious, and that the symbolic thoughts that we grammatize (or languatize) become conscious. The observation might go like this: if we can talk about X, then we are aware of X. The question then is: what is the relationship between language and consciousness?

If you trace back your your train of thought (during problem-solving or even in general behaviour), you might discover that there are actually thoughts where you previously thought there were not. For instance, if we asked Edmond Dantès why he thought that it would be a good idea to take the place of the Abbé Faría’s dead body in order to escape Château d’If, I believe he would be able to list the thoughts that I described earlier. Were these thoughts not there before we asked? Did they just appear after we asked him to backtrace his thoughts? Were they unconscious thoughts? Were they symbolic thoughts that although were conscious they had not yet the capacity to be talked about? My answer is that the thoughts were there all the time, although maybe not in a grammatical form and/or in a conscious manner.

What about when solving a puzzle like the wire puzzle of Situation 5? My guess is that even in this situation the brain is performing some sort of process akin to thinking but rather of taking place in the auditory cortex (the locus of thought) it occurs in the motor cortex. And as mentioned above, these thoughts (or better said: patterns, sequences of neural activity) can be conscious or unconscious as well as pure symbolic or grammatical. This latter case if we were to ask the solver to describe -verbally- their train of thought while solving the wire puzzle.