“Most observable patterns of nature arise from aggregation of numerous small-scale processes… Aggregation tends to smooth fluctuations.”

– S. A. Frank [5]

“Nature is both periodic and perpetual. One of the most basic laws of the universe is the law of periodicity.”

– Gyorgy Buzsaki [2]

“Pattern recognition was an important asset of neolithic technologies too. It marked the transition between magic and more empirical modes of thinking.”

– Hito Steyerl [16]

Most of the time, interesting questions arise when we ask things in the style of “what would happen if…?”, or if one tries to look at the world with the eyes of a Martian or any other otherwordly creature. (A creature like the Elytrecephalid in Fig. 1 created by the American illustrator Wayne Barlowe [1].) In this section, the question that interests us is the following: What would life be like in a universe without patterns? Here, we understand a pattern as a sequence of events or phenomena that occurs with certain periodicity. A universe where there are no patterns is a universe where all events occur in a random manner. In such a universe there are no annual seasons because everything happens randomly. There is no spring, summer, autumn or winter. There are no sowing nor harvesting seasons, and most probably, no agriculture as a consequence. There are no moon phases, the sun would rise sometimes, and others it would not. Most probably we wouldn’t exist in such an universe. We can survive in the universe because it exhibits a certain regularity, and we have an organ capable of identifying that regularity, namely our brain.

Isn’t it surprising that there are patterns in nature, that is, regularity both in the shape and in the occurrence of natural phenomena? Moon phases occur with certain regularity, as does the apparition of some comets, the annual seasons, eclipses, solstices and equinoxes. Moreover, the shapes of animals, their shells or fur colours, and even the distribution of leaves in plants exhibit some regular patterns. Just think of the spiral form of the Nautilus’s shell, the black and white stripes of the zebra’s fur, or the hexagonal patterns of honey combs. It is therefore surprising that there are patterns in nature. However, isn’t it even more surprising that we have a capacity to perceive such patterns? Not all animals in the world seem to be able to do this, that is, to perceive and recall the regularity of events and objects in nature; and it seems that the way that we -as a species- are able to perceive them is one of the skills -if not, the skill- that has put us at an enormous advantage in nature compared to other species. (Pattern-processing capabilities have also been identified in other non-human primates. Such capabilities include the capacity to create cognitive maps of a physical environment, the ability to distinguish members of the same species, and the identification of their emotional states based on facial gestures, and the use of gestures to communicate across members of the same species [13].)

It is because we are able to perceive patterns that we are able to know the right time for sowing and harvesting, or the occurrences of sea tides to name a couple of examples. Pattern recognition is perhaps one of the most important prerequisites for intelligent behaviour. Directly or indirectly, our capacity to recognise patterns lies beneath every invention or discovery that we have done as a species. The oldest computer that we know about, the Antikythera mechanism, is hypothesized to have been created for the purpose of predicting solar and lunar eclipses [6]; and we know that prediction is the result of pattern recognition. Agriculture, another major human invention, was the result of our capacity to identify the seasonal patterns within a year’s span.

Moreover, pattern recognition seems to lie beneath the neolithic revolution that changed prehistoric societies from following nomadic practices such as hunter-gathering to sedentary practices such as the development of agriculture. The development of the latter gave rise to an abundance of resources that required storage of commodity surpluses which eventually gave rise to the notion of property. In turn, the latter gave rise to the notion of bureaucracy and law [16].

Now let’s turn into the body. In addition to controlling the body and its systems, our brain is an organ that discovers patterns within its inputs. It does so mirroring the patterned structure of the world. We have an organ to detect, recognise, and memorise patterns because the natural world is full of them. This idea is similar to that of neuroscientist Dante Chialvo who stated that we have a brain whose dynamics are critical because the natural world exhibits such dynamics too [3, 17].

If we lived in a pattern-less universe, we simply wouldn’t able to survive. Moreover, we live within patterns. Our daily lives are full of patterns that we barely notice because of habituation. On average we wake up around the same time, our breakfast and other meal habits are similar across the days of the week, we take the same routes to go to and from work, et cetera. Our daily habits are patterns of activity that we develop not only to function within society, but also to minimise the anxiety produced by the necessity to take decisions in an environment filled with multiple options [7], a situation that is best summarised by a quote from philosopher Soren Kierkegaard: “Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom”.

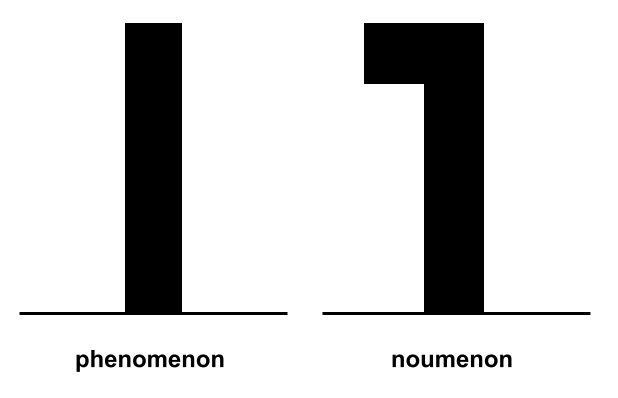

Now, let’s dive deeper into Kantian waters, and let’s ask ourselves the following question. Are there patterns in the Noumenon? As mentioned in this essay, the Noumenon is the world-as-it-is, the thing-in-itself, that is, the world independent of perception. Here we can ask ourselves whether there are patterns in the world-as-it-is, or do they appear only after the world is perceived? (“The hard problem to solve is whether time and space are situated in our minds only or whether they in fact exist independently of us”, says Gyorgy Buzsaki in [2].) There is little that we can say about the world of the Noumenon, but it seems that there are patterns in it that are perceived by our senses. Otherwise, if the patterns of nature were just an illusion, something that only appears after the world is perceived by our senses, then we would be in grave danger as a species.

Let’s consider a very simple example: if it were the case that in the Phenomenon we see in front of us a vertical object such as a pole against which we must avoid colliding (as in the left side of Fig. 2), but which is different in the Noumenon and of a different shape such that it has an extreme upper edge that stands out (as in the right side of Fig.2); if that were the case, then we would run the risk of crashing into the protruding edge of the pole, which we do not perceive in the Phenomena. In other words, such an edge appears invisible to us, although in the universe, in the world, in the Noumenon, that edge does indeed exist. Although simple, the example shows something meaningful: that the Phenomenon is close enough to the Noumenon such that we are able to navigate through the world by relying on perception and on our senses, that we are able to navigate through the world by relying on the representation that they, our senses, make of reality, of the world itself. Therefore, as the Phenomenon mirrors the Noumenon, patterns perceived in nature should mirror patterns existing in the world-in-itself.

noumenon.

Dear reader, consider this: there are things that you know that you know. This comprises the bulk of your knowledge. As well, there are things that you know that you don’t know. For instance, I know that I don’t know how to fly an aeroplane or how to perform heart surgery. As well, there could be things that you don’t know that you know, and these are weird situations indeed; but it could be the case that deep beneath our minds resides some sort of instinctive knowledge that some of us are not aware of yet. Lastly, there are things that we don’t know that we don’t know; these are the unknown unknowns, and these are the most dangerous things in the epistemic world.

Considering the things that we don’t know that we don’t know let’s ask ourselves the following: What if there are patterns that we are unable to see because of our limited perspective of nature? The time scale of human affairs allows us to be able to identify certain patterns. The time scale of human affairs consists of seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, and years; whereas our spatial scale is that of centimetres, meters, etc. (In contrast, the scales of a nerve cell is that of milliseconds and nanometres, whereas those of astronomical objects are in the orders of millions of years and light-years.) We extend both our spatial and temporal scale by using science and its tools. Having said that, perhaps there are some patterns in nature that escape our sight because they do not fit into our scales, and haven’t been yet considered by the eye of science. What if events that we believe occur only once are actually cyclical but because of our limited perspective we are unable to perceive them? What if the emergence of a virus or another type of pathogen is something that occurs with some frequency for reasons we do not fully understand? What if some weather events are of a a cyclical nature? For a fly, winter is a once-in-a-lifetime event. Unlike us, it doesn’t know that it is a cyclical event. However, a fly doesn’t know that it doesn’t know possibly because it doesn’t know anything at all. More to my point: a fly’s mind doesn’t allow it to grasp knowledge K. In the same way, there could be some knowledge K′ that is inaccessible to our minds, but it is for another superintelligence (think again of the Elytracephalid in Fig. 1, or any other organism above us on the Kardashev scale [10] of intelligence). Knowledge K′ is part of our unknown unknowns: we don’t know that we don’t know.

For instance, we have fairly recently started to understand how glaciations occur on Earth, and to understand how something such as an ice-age which was once thought to be a one-time event in Earth’s history is actually a cyclical event that can be predicted with certain accuracy by considering, among other things, the Milankovitch cycles which measure the effects of Earth’s motion (such as rotation and tilting) over its climate [15].

We live in a world full of patterns, thus we live in a world full of meaning. The brain tries to find structure within it. Is there a particular brain region devoted to pattern recognition? The fusiform face area (FFA) is a region in the visual system in the occipital lobe of the brain devoted to -well- recognising faces. Other than the FFA, no other area has been found to explicitly recognise a particular form found in nature, and that is because probably most of the brain is devoted to recognising patterns, where a pattern is not only a pattern of stimulus coming from the exterior world via the senses, but also neural patterns generated elsewhere within the brain. From an evolutionary point of view, three regions in the human brain reveal significant size expansion compared to other primates, and have been related to superior pattern processing in humans. These areas are: the visual cortex, the prefrontal cortex, and the parieto-temporal-occipital juncture. These regions are mostly involved in pattern processing of sights and sounds and their codification as written and spoken languages [13].

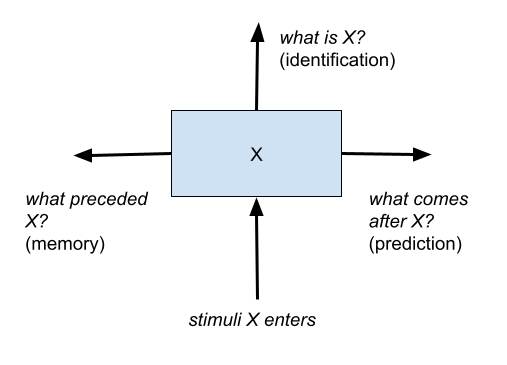

At every time, the brain, or better said, its circuits are doing the following with its input (Fig. 3). Upon the entrance of stimulus or neural pattern X to a neural circuit, the neural circuit performs:

- Identification: the circuit identifies the pattern with something it has already encountered, or with something similar that it has encountered previously. In case it hasn’t encountered it before, it stores it as a novel pattern.

- Recollection: making use of memory, the circuit is able to keep track of the patterns that preceded the current pattern and link them temporally.

- Prediction: based on memory, the circuit is able to predict the pattern that will come after the current pattern.

These three operations are already a consequence of pattern recognition in the brain and its circuits, and are at the core of every other neural algorithm performed by the brain over its input, that is, they are essential operations of the brain.

At times it seems that a way to understand a particular brain function is to look at the cases when the function is absent or impaired. We can marvel at the brain’s capacity to discover patterns in nature also when this capacity is disrupted as a consequence of neural disease. In the specific case of pattern recognition, we can mention two conditions: apophenia and pareidolia. The first refers to a situation in which an individual has an increased tendency to identify patterns where there are none, and to perceive meaningful connections between unrelated events. In other words, it refers to recognising patterns within random data. This condition is particularly increased in people with a tendency to believe and be attracted to conspiracy theories. Also, this condition has previously been identified as one of the early stages of schizophrenia. Pareidolia, on the other hand, is a type of apophenia in which there is an increased tendency to perceive signal where there is only noise. For instance, to perceive images or sounds where there is only random stimuli. Examples of this are the perception of shapes in clouds or religious icons in rock formations, or the perception of a face or a rabbit in the face of the moon, Jesus in a toast, or the Virgin Mary in a tortilla [11]. However, face pareidolia, that is, the increased tendency to see faces in random stimuli, has revealed the role of feedback connectivity from higher brain structures such as the prefrontal cortex, to lower ones such as the primary visual areas, and the aforementioned FFA region [11]. This highlights the importance of bidirectional information flow across networks of the brain.

Illusory perception is common. The triggering of perception of a known object or pattern by random stimuli is not entirely wrong. We are the descendants of those human beings that didn’t wait to confirm whether the animal behind the bushes was a predator or not. The other type, those human beings that waited to gather more evidence regarding the presence

or absence of a tiger behind the bushes were eaten by it, and didn’t have a chance -thankfully- to spread their genetic material across the ages. We are wired to complete a pattern with so few incoming stimuli, or in machine learning terms, with few shots. (This could also explain why some of us have a tendency to see the glass half empty, and to think of the worst as soon as tiny bad omens appear. But this is the topic for another essay!)

Pareidolia and apophenia refer to conditions where the brain overreacts to external stimuli perceiving patterns where there is none. The opposite also occurs, namely, a failure to recognise patterns when they are present. It has been suggested that psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease are a consequence of an impaired capacity to process patterns [13].

Pattern recognition is an important aspect of brain function, and it seems that already basic circuits in the brain are performing it over their inputs whether these come from the senses or another brain region. Pattern recognition seems to be closely intertwined with prediction. Both essential requirements for intelligent behaviour. If I asked you to identify the pattern shown in Fig. 4, most probably you would answer that it is the number five. You have performed both pattern recognition and prediction. You correctly recognised the pattern even when incomplete, because you predicted a black stroke where the number five looks broken.

One last word about patterns. We seem to love them. Music is probably the best example of something made up of patterns that gives us pleasure. Our understanding of patterns transcends the cognitive and enters the aesthetic. Perhaps there is an interplay between pattern recognition, prediction and the release of pleasure molecules such as dopamine [18, 19]. The element of surprise found in certain types of music, for instance, the use of odd-time signatures, breaks expectation and prediction during the experience of music, and makes it more pleasurable and interesting to many people. This suggests that in order to find music enjoyable it should have the right amount of pattern recognition and expectation breaking. Lastly, a life without music would be a mistake, said Friedrich Nietzsche. Perhaps we can say the same about an universe without patterns.

References

[1] Wayne Douglas Barlowe and Ian Summer. Barlowe’s guide to extraterrestrials. Workman Publishing Company, 1979.

[2] Gyorgy Buzsaki. Rhythms of the Brain. Oxford university press, 2006.

[3] Dante R Chialvo. Life at the edge: complexity and criticality in biological function. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.11737, 2018.

[5] Steven A Frank. The common patterns of nature. Journal of evolutionary biology, 22(8):1563–1585, 2009.

[6] Tony Freeth, Yanis Bitsakis, Xenophon Moussas, John H Seiradakis, Agamemnon Tselikas, Helen Mangou, Mary Zafeiropoulou, Roger Hadland, David Bate, Andrew Ramsey, et al. Decoding the ancient greek astronomical calculator known as the antikythera mechanism. Nature, 444(7119):587–591, 2006.

[7] Catherine A Hartley and Elizabeth A Phelps. Anxiety and decision-making. Biological psychiatry, 72(2):113–118, 2012.

[10] Nikolai S Kardashev. Transmission of information by extraterrestrial civilizations. Soviet Astronomy, 8:217, 1964.

[11] Jiangang Liu, Jun Li, Lu Feng, Ling Li, Jie Tian, and Kang Lee. Seeing jesus in toast: neural and behavioral correlates of face pareidolia.

Cortex, 53:60–77, 2014

[13] Mark P Mattson. Superior pattern processing is the essence of the evolved human brain. Frontiers in neuroscience, page 265, 2014.

[15] Maureen E Raymo and Peter Huybers. Unlocking the mysteries of the ice ages. Nature, 451(7176):284–285, 2008.

[16] Hito Steyerl. A sea of data: Apophenia and pattern (mis-) recognition. E-flux Journal, 72, 2016.

[17] Enzo Tagliazucchi and Dante R Chialvo. The collective brain is critical. arXiv preprint arXiv:1103.2070, 2011.

[18] Laura Ferreri, Ernest Mas-Herrero, Robert J Zatorre, Pablo Ripollés, Alba Gomez-Andres, Helena Alicart, Guillem Olivé, Josep Marco-Pallarés, Rosa M Antonijoan, Marta Valle, et al. Dopamine modulates the reward experiences elicited by music. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(9):3793–3798, 2019

[19] Catalina Valdés-Baizabal, Guillermo V Carbajal, David Pérez-González, and Manuel S Malmierca. Dopamine modulates subcortical responses to surprising sounds. PLoS biology, 18(6):e3000744, 2020