Artificial General Intelligence or AGI is probably the holy grail of artificial intelligence. The term refers to the capacity of systems to learn a diverse range of behaviours without forgetting what they have already learned, and being capable of learning new ones.

To know why this is important let’s consider the opposite case. Take for instance AlphaGo, a system that was designed and trained with the particular goal of playing the game of Go and nothing more. That is, AlphaGo wouldn’t be able to play any other board game, or doing anything else for that matter. And even at playing Go it doesn’t do it the way a human would do it. The output of AlphaGo are the details of the next move that a human player, reading such output would have to perform on a board. If AlphaGo were a person then it would be someone who is unable to move any limb but it’s only able to perform intellectual tasks, and even there it’s quite limited as he or she would only be able to perform intellectual tasks devoted to the particular game of Go. If AlphaGo were a person, he or she would actually be a very specific and limited area of the brain, and only that. Perhaps a quadriplegic whose brain function is limited to that of the game of Go.

A true Go player, or any other board game player, knows not only the rules of the game they’re playing but also they know how to use their bodies, how to move their arms to reach a piece, how to move their hands and fingers to grasp a piece, etc.; this is a set of skills that are generally overlooked by artificial intelligence researchers. This might sound absurd to the reader, but actually, as it was said elsewhere, the hardest problems for artificial intelligence are the easiest problems for human beings, and vice versa. We take for granted the problem of motor control when it comes to extending an arm to grab a piece; deeming it trivial, and focusing on the problem of playing a board game (such as Go) optimally.

A generally intelligent artificial agent would be one that solves, among others, these two problems: the quote-on-quote intellectual problem of winning a match of a particular board game, and the motor problem of moving its pieces (and perhaps also interact with its opponent). Both behaviours should be adaptive in the sense that it doesn’t matter where the match is played, what kind of board, colour, pieces, environmental situation: whether the game is played standing or seated, in a bar or in a café; the system should adapt its behaviours to each situation.

Do we have the algorithms, methods, techniques, and hardware to create such a system? My stand in this regard is that despite the impressive milestones in machine learning, we are not close to achieving the goal of AGI for reasons that I will enumerate below. Such reasons also point out to the fatal flaws that modern machine learning face today.

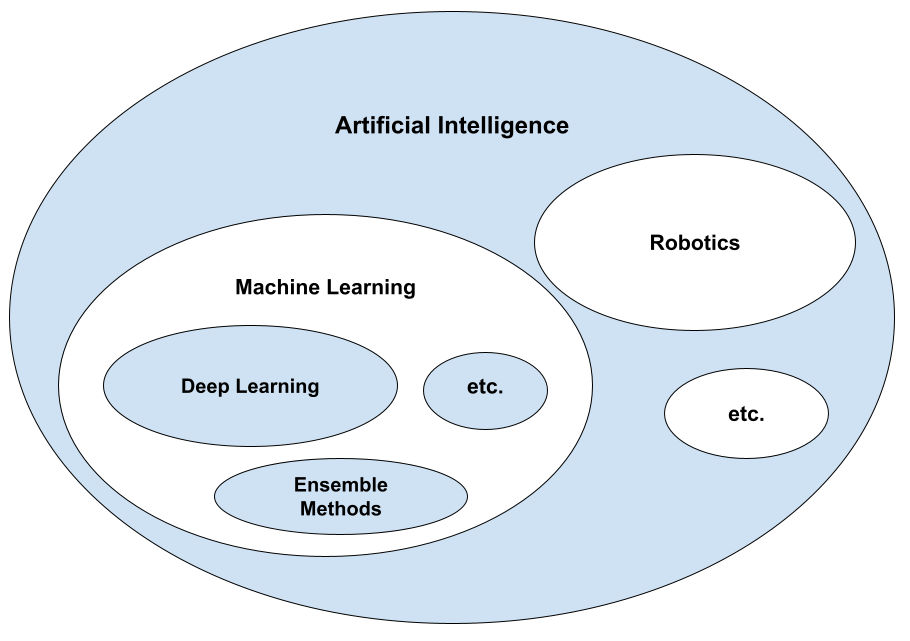

Let’s start by differentiating machine learning from artificial intelligence. Machine learning (ML) is the field of artificial intelligence (AI) that uses statistical techniques on -big- data to make systems produce intelligent behaviour (see figure below). Machine learning is behind the most impressive results in artificial intelligence that we have seen in recent times, including things like large language models (LLMs) and text-to-image models. However, ML suffers from a few fatal flaws which are essential for any system to exhibit AGI.

Such flaws are the following:

1. Data hunger: Loads of data, most of it labelled, must be collected to train models. This without mentioning the dubious ways in which such data is collected which include scraping content from the web without giving proper attribution to its sources.

2. Black-box inference: The issue is that we cannot know why a particular model (specially those based on artificial neural networks) arrive to the predictions (i.e. inferences) they do. And thus, for example, a financial institution might not know the reasons why its system denied a loan to a particular individual.

3. Discontinuous learning: Learning has to be split in two different phases: training and inference. Once a system is trained, it is deployed to perform inference on input data. A deployed system loses its capacity to learn from new data. Therefore, a new training phase must be launched upon the arrival of new observations. After retraining, the cycle repeats.

4. Large carbon footprint: Modern ML models consume large amounts of electric power for both training and inference. For instance, the power consumption to train LLMs, such as GPT-3, was equivalent to the power consumption of a small city [1, 2, 3].

So, what is the issue with modern ML? Is it its computing medium based on silicon following the Von Neumann architecture (see below)? Or is it its algorithms, or a combination of both? The issues enumerated above are highlighted when we compare artificial intelligent systems against natural ones. The human brain runs on an energy budget of around 20 watts of power [4]. It does not need to stop inference in order to acquire new knowledge. That is, the phases of learning and inference are intertwined. Alright, someone might argue that the purpose of sleeping (which could be considered a quote-on-quote shutdown of the brain, or of some of its subsystems) is to consolidate new knowledge. This observation is not the case. We do not need to go to sleep after burning ourselves in the kitchen in order to avoid a touching an object that just left the oven. In most cases, we require very few observations to acquire new knowledge because we are taking advantage of previously acquired knowledge(*). And this points out to a particular feature of (human) knowledge, that of exhibiting the property of rich gets richer: the more knowledge one has, the easier it is to gain even more knowledge. Finally, most of the time we human beings are able to backtrace our argument chain to describe how we arrived at a particular claim, conclusion or inference. Here, some arguments about the difference between conscious and unconscious thought can be brought up. However, with some training and/or help of properly trained people we might be able to make the unconscious conscious, and thus explain the reasons behind a specific claim or behaviour.

So, if natural intelligence, and that which results from the human brain, overcomes the flaws mentioned above, why aren’t we building systems based on it? This question points out to a desiderata, a wish-list of computational properties that we would like to see in a system. We would like to have a device, be it digital, electronic or some combination of organic and mechanical, but in principle artificial, which satisfies the following computational properties; such a list is not exhaustive but should point out to some essential characteristics:

1. Continuous learning: the system is able to learn continuously from its inputs without having to be shut down for retraining.

2. Unsupervised learning: the system learns without supervision. It implements some sort of semi-supervised learning in which the system poses hypotheses, tests them, and learns from them.

3. Data-lean learning: the system learns from small samples of data rather than being exposed to humongous amounts of it to learn its particular statistical properties.

4. No catastrophic forgetting: the system implements continuous learning without forgetting what it has already learned.

5. Sequential learning: the system is able to learn the sequential nature of its inputs, that is, to learn a sequence when there is one, and identify when there is none. (It could be argued that all data is in nature sequential, and that static data is a particular case of input data in which the temporal dimension is discarded.)

6. Invariant representation formation: the system learns abstract representations of knowledge, in which the first step is to learn invariant representations of its input. It is able, for instance, to identify an apple in different contexts, environments or scenarios, without thinking that an apple in the kitchen table and an apple in the desk are different objects. Let’s contrast this with some types of adversarial attacks to computer vision systems in which if an image is flipped, the system outputs a different inference.

7. Imitation learning: the system possess an elaborated representation of itself and from the entities surrounding it. It also acknowledges itself within a social structure, and it’s able to learn by imitating others.

8. Provides motor control: the system solves the control problem. It is able to control an external body that carries it through the world.

9. Spontaneous generation of sequences: the system is able to generate sequences spontaneously. Such sequences comprise the learned invariant representations and form a basis for the hypotheses required for semi-supervised learning. It seems that babies generate their own -motor- data when we see them moving their limbs while lying, and also when we see them grabbing objects and then tossing them. They are generating their own data to learn how to control their bodies. What is their teaching signal? Pain. Pain provides the signal their require to adjust their motor behaviour. Lastly, so-called generative AI is all about generating data (images in the case of text-to-image models or text in the case of LLMs) from user prompts.

10. Planning: the system has goals and is able to plan in order to achieve those goals. In order to achieve this, the system is able to represent a goal in a meaningful way to its inner mechanics.

11. Decision making: the system can make decisions and plan its actions.

We haven’t mentioned how a system that exhibits such properties would look like, and what are the medium and algorithms underlying it. Probably, a system that exhibits such properties would have solved the credit assignment problem, among other open questions of modern ML.

Now that we have described the desired properties of our system, let’s ask ourselves how can we implement this. Should we take natural intelligence as a reference to build such a system? Modern ML techniques implement some of these computational properties. For instance, Numenta’s Hierarchical Temporal Memory model (HTM) exhibit continuous, sequential, unsupervised learning [5]. However, the HTM model has a more-or-less self imposed constraint, namely, that it aspires be as biologically plausible as possible, and this constraint rather than benefiting it, impairs it (see two figures below). Other modern ML techniques, such as Deep Learning, despite being inspired by biological neurons little have in resemble to their natural counterparts. However they are behind the most (if not all) the impressive results in AI that we have seen in recent years. The combination of deep learning with techniques such as reinforcement learning has made possible the AI revolution that we are experiencing nowadays. These techniques have little resemblance to biological neural networks, but have yielded outstanding results such that one wonders if we should mimic nature at all. However, one constraint that modern ML techniques have is that they run in a Von Neumann (VN) architecture, be it in a CPU or a GPU.

The VN architecture, named after the Hungarian mathematician John von Neumann (see figure below) is the hardware architecture in which electronic computers (or anything running on a microprocessor, including your smartphone) are based on. As such it entails certain bottlenecks, being the data bus the most critical of them. Compare this to the parallel, asynchronous and event-driven nature of the computing medium that is the nervous system. Machine learning systems running on a VN architecture are affected by such bottlenecks. Therefore, some computational alternatives have been proposed in recent years, when it comes to maximising hardware power in ML scenarios. Such alternatives include in-memory computation, and the design and implementation of AI-accelerators in application-specific integrated circuit (ASICs) and field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs), among others in a nascent field at the intersection of artificial intelligence, electronics and material physics.

In my opinion, ML is about to hit a wall: a hardware wall. The situation makes me think of in the figure below, in which we can only pick two options from the three presented.

At the end what we want is that the system satisfies our computational desiderata even if is not biologically plausible nor it is implemented in a Von Neumann architecture. This is the David Marr’s approach, the engineering approach. We care for the algorithms and the problems they are solving rather than trying to mimic nature to every detail. Deep Learning (in combination with reinforcement learning and other methods) is the best ML technique that we could develop within the VN-architecture paradigm. If we want to circumvent its deficiencies (see above) we might need to look elsewhere for the right medium and probably the right algorithms too. Most probably, a system that satisfies the desiderata outlined above doesn’t look like any method or technique that we have, nor it runs in a medium such as the VN architecture. These unknown unknowns are what keep us AI researchers motivated.

(*) In other situations this is not the case, as anyone learning a new language or learning how to play a musical instrument would know, sometimes it takes years to learn either of these skills.

References:

[1] Emma Strubell, Ananya Ganesh, and Andrew McCallum. Energy and policy considerations for deep learning in nlp. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.02243, 2019.

[2] David Patterson, Joseph Gonzalez, Quoc Le, Chen Liang, Lluis-Miquel Munguia, Daniel Rothchild, David So, Maud Texier, and Jeff Dean. Carbon emissions and large neural network training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.10350, 2021.

[3] Alexandra Sasha Luccioni, Sylvain Viguier, and Anne-Laure Ligozat. Estimating the carbon footprint of bloom, a 176b parameter language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.02001, 2022.

[4] Vijay Balasubramanian. Brain power. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(32):e2107022118, 2021.

[5] Jeff Hawkins and Subutai Ahmad. Why neurons have thousands of synapses, a theory of sequence memory in neocortex. Frontiers in neural circuits, page 23, 2016.