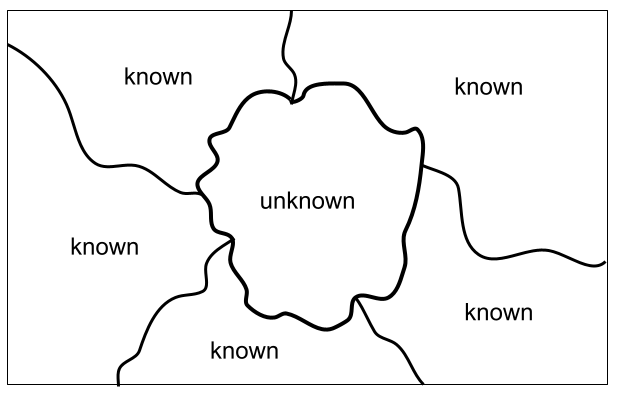

Let’s suppose that you’re given the task of separating images that contain -say, for instance- cats from those that don’t. This should be easy given that you know what a cat looks like. Let’s suppose that now you’re given the task to separate images containing an object that you don’t know, say for instance a kwyjibo, from those images that do not contain it. To do so, you first need to learn what a kwyjibo is. For that purpose, you are given a bunch of images labelled kwyjibo and not-kwyjibo for images containing and not-containing kwyjibos, respectively. If such images look like natural images, that is, images that you encounter naturally in the world, then you would rely in your notions of foreground, and background in order to separate the figure of a kwyjibo from the background in a single image. Moreover, you would make use of existing knowledge of other objects within the image in order to locate the unknown figure of a kwyjibo inside the image. And thus, you would segment the image in areas of known and unknown objects just like in the Fig.1 below. You would then assume that the object kwyjibo comprises the area deemed as unknown. You would also gather the commonalities in all the unknown areas from images labelled as kwyjibo. If the set of images is well-constructed, and this refers to the role of data in machine learning which is something we will talk about in another post, then it will probably take you just a few images to learn what a kwyjibo is. So, to accomplish the task of separating images that contain a previously unknown object from those images that don’t you made use of notions such as background and foreground, in addition to knowledge of other objects that might appear in the images. Not to mention that you also required a curated set of images.

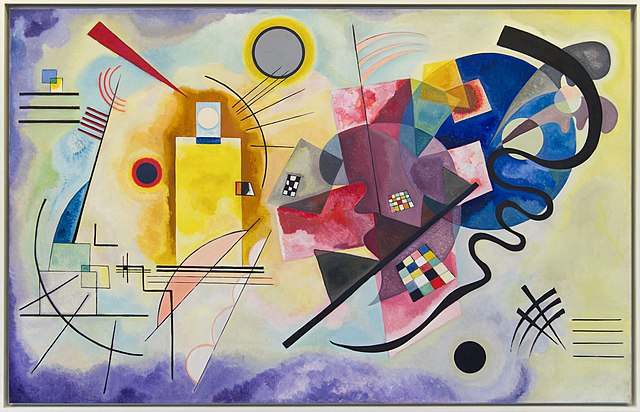

Now, let’s suppose that you cannot distinguish figure from background, actually let’s suppose that you don’t know anything about foreground and background, that you don’t possess such concepts. Let’s suppose that when you look at an image it actually looks to you like a painting from the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky (see Fig.2 below). Let’s suppose that you live in an universe where images like that are natural images, that is that the objects they portray occur naturally in this universe.

In this case, how do you know which images contain a kwyjibo and which do not? As I said, the first thing is to know what a kwyjibo looks like. Here, however, you don’t know what in the image belongs to the foreground and what to the background. You don’t know where the figure ends and the background begins. You start by collecting the commonalities, the recurring patterns in images that are labelled as kwyjibo, but you also consider the images labelled as not-kwyjibo so that you can confirm that your hypotheses regarding the patterns found in the former set actually refer to kwyijibisness. This time, because you know nothing about background and figure, the task might require more than a handful of images than in the previous case.

So, the answer to the question: why do humans require less examples to learn a new animal from a picture or a series of them when compared to computers? seems to point to the fact that we rely on previous knowledge to acquire new knowledge. In particular, we know the concepts of foreground and background. We can tell the limits between object X and not object-X even if we don’t know what object X is (see Fig.1 above). Also, we rely on what we know about quote-on-quote animality to learn about a new animal. We know that animals might possess fur or feathers, have wings or walk in four legs, etc.

These observations apply to natural images, those that our brains evolved to process and which we have seen most of our lives. It wouldn’t apply, for example, to Kandinsky-type images. If we lived in an universe where Kandinsky-type of images were the norm, i.e. this kind of images were actually natural images, then we would be in a situation similar to that of our artificial neural networks.

An artificial neural network (ANN) trained to solve a computer vision task knows nothing ab initio about foreground and background, nor anything about animals or other objects that might appear within an image. They most learn these concepts through collecting recurring patterns in previously-labelled images1. Therefore, it is no surprise that they need to see as many and as diverse images pertaining a specific class or object as possible. We would be better off if we taught our ANNs or equipped them to know concepts such as foreground and background. Stuff that is already done by image-segregation systems, but seldom put in use to aid the process of image classification nor to acquire new knowledge. This highlights a major flaw of ANNs, they make use of knowledge -say to classify an image- but don’t expand it; they do not possess a way to learn continuously from their inputs.

How did we learn to distinguish foreground from background in the visual stimuli entering our eyes? My guess is that there is a genetic component on it. Our visual system has been developed and refined over the aeons through evolution. We possess neural circuits devoted to this task, and whose topology was carved by the principles of Darwinian evolution. As well, let’s not forget that the first years of our lives are devoted to learning a myriad of skills that we usually take for granted. One of these might be the capacity to tell figure from background in natural images. The outcome is that we need just a few examples to learn a new -visual- concept (for instance, what a kwyjibo looks like) compared to the millions of images required by our modern computer vision systems.

The comparison between human-learning and machine-learning is a bit unfair. Humans might require less training examples but it takes more years to train than a computer running state-of-the-art machine learning algorithms in a skill such as image segmentation. Keep in mind, for instance, that human beings are the mammals with the longest period of childhood in the whole animal kingdom. In contrast, machines might require more training examples, loads of them, but it take less time to train.

One for the human beings though: the architecture of the nervous system makes it such that one piece of knowledge is used everywhere. Knowledge of background and foreground is used extensively in the brain: it is used for navigation, for acquiring knowledge of new concepts or objects, for classification/recognition of known objects, and more. Also, let’s not forget that the nature of incoming stimuli to the nervous system is sequential, that is, streams of information, rather than static images as in the case of most ANNs. Our brains make a remarkable job at distinguishing figure from background on real-time, and also at using such knowledge to acquire more of it.

1Actually, there is no actual learning of concepts, but only pattern recognition.