What is a neuron good for? What was Mother Nature thinking when she created it? We know that the neuron emerged from ancestral secretory cells [29] and evolved at least 5 times in history, and thus its origin cannot be traced to a common ancestor [29, 2, 21].

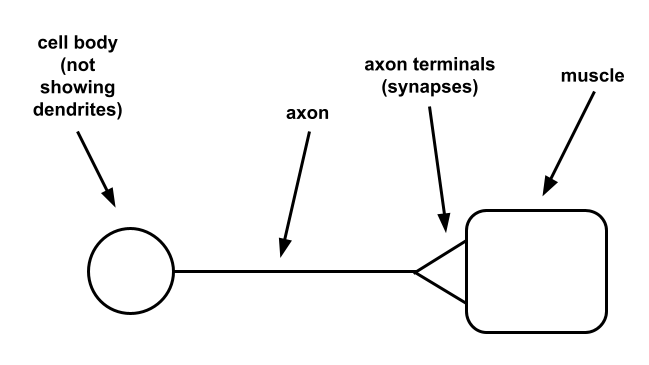

In simple organisms where a nervous system or nerve cells are present these serve as a mechanism to provide the system with perception and action. In this simplest of cases a nerve cell resembles the abstraction depicted in Fig. 1, where a single cell is responsible for both perception and action. As soon as the neuron perceives something, that is, as soon as it becomes active the neuron in turn activates the muscle1. In this case, the neuron acts like a quote unquote button that activates the muscle, like a button to trigger the opening of a door. This simple nervous system implements the following logic: if neuron becomes active then activate muscle. This, by the way, is the basic principle of a reflex-type circuit.

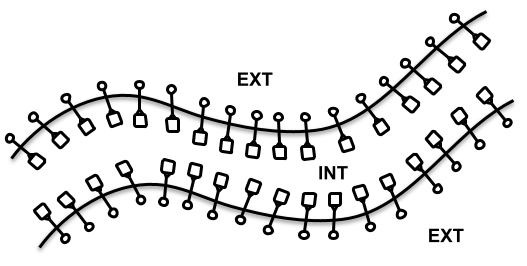

Let’s imagine a simple organism that implements this simple nervous system, something like a nematode that possesses cilia-like structures through which this organism perceives the environment, and reacts to it immediately by moving its muscles and thus propelling the organism forward (see Fig. 2). The behaviour of such an organism is simple and predictable. An organism this simple probably wouldn’t survive in a world like ours. It will probably fall prey easily and/or it wouldn’t have the right mechanisms to look for food or mates.

system.

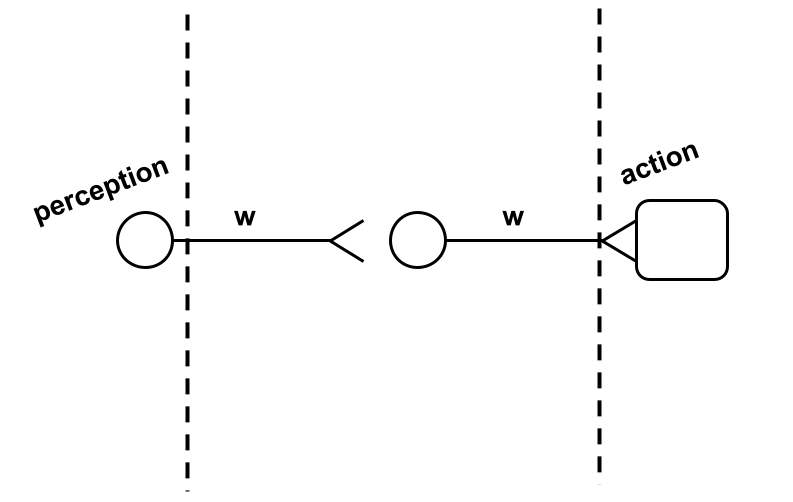

What happens when we add another neuron in between perception and muscle as in Fig. 3? Now the response of the neuron connected to the muscle becomes modulated. It will only do so when properly driven by the first neuron, the one doing all the perception. Its activation now depends on its threshold and how much activity it receives from the perception neuron. How much activity the motor neuron receives from the perception neuron is represented by the letter w in Fig. 3 which stands for synaptic weight. Synaptic weights represent the amount of influence that one neuron has over another. The only missing ingredient in our simple 2-neuron system would be a learning mechanism that modulates the synaptic weight between the two neurons. Now the logic implemented by this simple neural circuit is: the muscle will be activated if the motor neuron is sufficiently driven by the perception neuron, and this will depend on the environmental circumstances detected by the latter neuron. Now the behaviour becomes more complex, and thus less predictable, than in the first case.

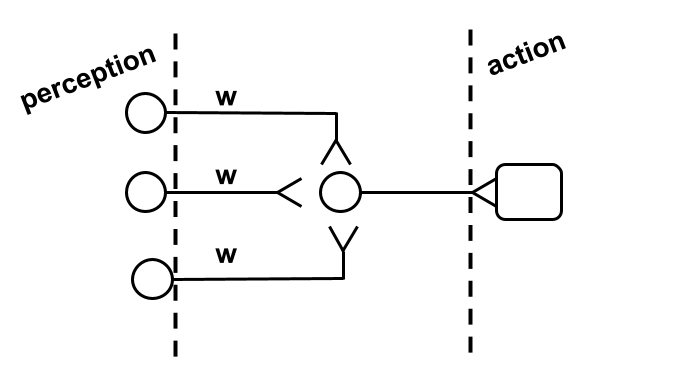

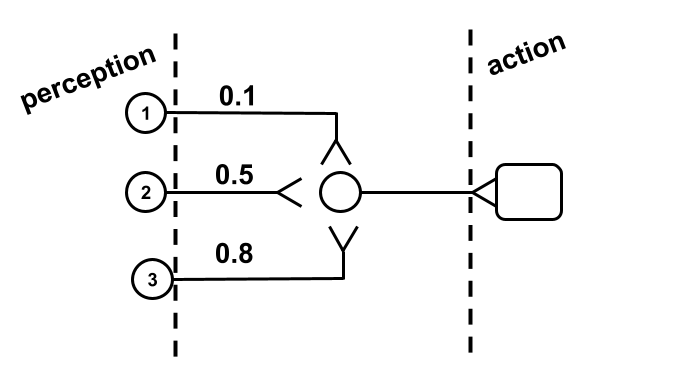

Now, let’s consider the situation depicted in Fig. 4. Here we have not only one but three neurons perceiving the environment, and the three of them are connected to the motor neuron. Each of them with a different amount of influence over the motor neuron denoted by their corresponding weights w in Fig. 4. The capacity to drive the motor neuron will depend on its inner threshold and the influence that each of the perception neurons have over it.

Let’s suppose that the neural circuit in Fig. 4 now looks like the one depicted in Fig. 5, where weights from perception neurons to motor neuron are shown. Remember that the weights represent the amount of influence from one neuron to one it connects to, or in neuroscientific terms: the influence from presynaptic- to postsynaptic neuron. To simplify the discussion, let’s say that this influence takes values from 0 to 1, where 0 represents no-influence and 1 represents maximum influence. If our motor neuron has a threshold of 1, that is, if it needs an accumulated input of 1 in order to become active, then no presynaptic neuron would be able to activate it by itself. It requires the joint activity of at least neurons labelled 2 and 3. Why would the presynaptic neurons 1 to 3 would have such influence (small or large) over the motor neuron? That depends on where are these presynaptic perception neurons are located in the organism. Each of them represent a particular case within the perceptual landscape of the organism. They represent the presence or absence of a particular case, and when such a case is present they also include the importance that the presence of the case has within the organism. How such importance is determined? A simple answer would be that is determined through learning, that is, through neural activity, but also it might also be determined by genetic factors.

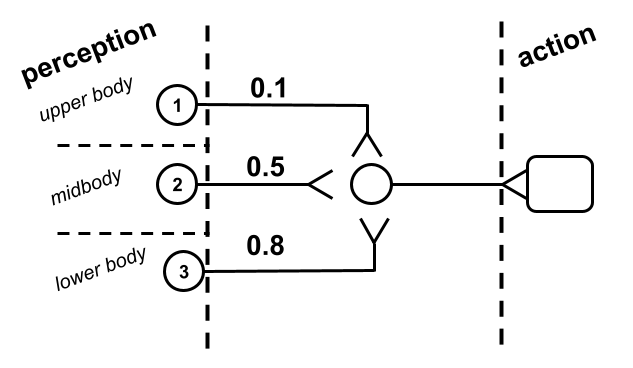

Now, let’s suppose that these perception neurons receive tactile information, that is, they are placed through the skin of the organism as in Fig. 6. Neuron 1 receives haptic information from the upper part of our fictional organism’s body, whereas neuron 2 does it from the middle of the body, and lastly neuron 3 does so from the lower part of the body. In our particular case it wasn’t Nature, rather I, who determined the importance of the contribution that each of these perception sites have over the motor neuron. The logic that this circuit implements is the following: activate muscle, if at least we perceive tactile information coming from both mid- and lower-body.

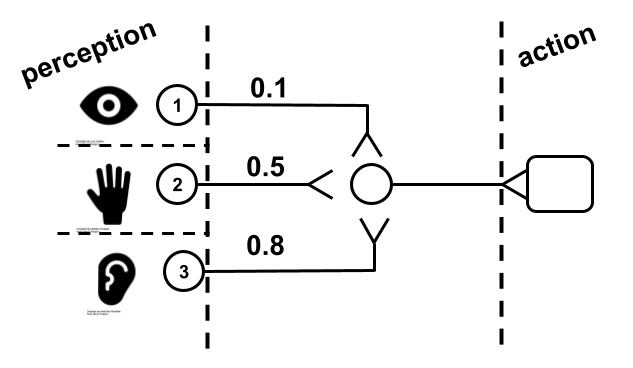

In another scenario, our interneuron could also be receiving multimodal information, for instance, coming from vision, touch and hearing (see Fig. 7). In our particular example, the information incoming from hearing has more importance that the information coming from the other two senses. However, information coming only from hearing is not enough to trigger the activation of the muscle. This particular interneuron also requires information from touch to activate the muscle. The logic that this circuit implements is the following: if information coming from hearing coincides with information coming from touch, then activate the muscle.

modalities

What information coming from hearing and what information coming from touch? That depends on where the neurons are located in the organism, and to what type of perception are they sensible to. In other words, it depends on their receptive fields. In these oversimplified examples, information was more-or-less interpretable. In reality, in living organisms where neurons receive thousands of connections2, the situation is way more complex not only because the brain is processing information coming from the senses but also from the intermediate stages between perception and action. The brain creates intermediate representations of information coming from perception thus complicating the interpretation of what set of cases or logic a particular neuron is responding to. Cases in the real -human- brain are not as straightforward to interpret as it would be if we came across a neuron that responds to a situation or object that possesses meaning in the scale of human affairs3. Rather, a neuron might evaluate a case involving a particular retinal ganglion cell, or a particular auditory hair cell in the cochlea, or a particular neuron or column within the neocortex. Case-interpretation is therefore out of the question.

How does this perspective of a neuron’s function fit with the debate around temporal versus rate coding? How does it fit in light of spiking behaviour such as bursting, back-propagating action potentials, and dendritic spikes? Is the neuron conveying information through its spiking patterns? Or does it act as a gateway, a gatekeeper that will only become active -and thus, attempt to activate subsequent neurons along its downstream- unless triggered by the right cases? If this is the case, why the bursting? Why the dendritic spiking, etc? These spiking behaviours are inline with the observation that neurons are case evaluators. They, however, reflect the complexity undergoing neural computation. Bursting can be interpreted as a response from a presynaptic neuron to a case or series of cases in which it is of extreme urgency to activate neurons in its postsynaptic vicinity. In turn, dendritic spiking can be interpreted as a pre computation of cases that occurs in the dendritic tree of a neuron; a pre-computation that has as input information coming from downstream areas, that is, feedback information.

Let’s not forget that the time-scale of neural tissue is that of milliseconds4, whereas the time-scale of human affairs is that of minutes and hours5. We have been trying to understand a system comprising billions of elements, whose operation lies at the time-scale of milliseconds (and its size, at the scale of micrometers) by looking at its behaviour on average without considering that the system, at the scale of its working unit, is doing a simple thing, namely, case evaluation. The complexity of the situation lies in the fact that the system comprises billions of case evaluators, and each of them can evaluate on average 7 thousand different cases.

The challenge as neuroscientists remains the same with whatever perspective we take regarding neural computation. The challenge is to explain cognitive phenomena such as reason, imagination, intelligence, emotion, etc. in terms of neural information processing based on rate coding, temporal coding, or case evaluation.

References

[2] Detlev Arendt, Paola Yanina Bertucci, Kaia Achim, and Jacob M Musser. Evolution of neuronal types and families. Current opinion in neurobiology, 56:144–152, 2019.

[11] David A Drachman. Do we have brain to spare? Neurology, 64(12):2004–2005, 2005.

[21] William B Kristan Jr. Early evolution of neurons. Current Biology, 26(20):R949–R954, 2016.

[29] Leonid L Moroz. On the independent origins of complex brains and neurons. Brain Behavior and Evolution, 74(3):177–190, 2009.

[32] R Quian Quiroga, Leila Reddy, Gabriel Kreiman, Christof Koch, and Itzhak Fried. Invariant visual representation by single neurons in the human brain. Nature, 435(7045):1102–1107, 2005.

- I recently learned that German biologist and pioneer neurophysiologist Nicolaus Kleinberg discovered polarized cells consisting of two components: one perceptual and one motor-like; He called this cells “neuromuscular”, and suggested that they might represent an ancestral stage toward the development of pure neuronal and muscular cells [29]. ↩︎

- On average a neuron in the neocortex possesses 7 thousand synapses [11], that would

be 7 thousand cases that on average -and following our discussion- a neuron is able to

process. ↩︎ - However, the idea of the so-called Jennifer Aniston neuron [32] is precisely this. ↩︎

- Although their inner workings operate at a nanosecond time-scale. ↩︎

- This is natural as our behaviour is based on the dynamics of neural tissue, and not

the other way around. ↩︎

One thought on “Neurons are case evaluators”