Is one kind of neural circuit required to process visual information, another type to parse speech, and yet another to sequence movements? Or do circuits with different functions share common organizational principles?

Kandel et al. [1]

In the previous post, we talked about the role of the nerve cell as a case evaluator for stimuli coming in and out of the nervous system. We mentioned that some cases are of a larger importance to the system than others. Who or what sets this importance? Let’s recall that some neurons have more influence over their postsynaptic neighbourhood than others, and such an influence could have been set by some genetic factor. However, it would also be beneficial to the system to possess a mechanism by which the influence is set by the activity of the organism. Such a mechanism evaluates the activity of a neuron or a group of them and modulates their influence based on some kind of metric. This is mechanism is learning.

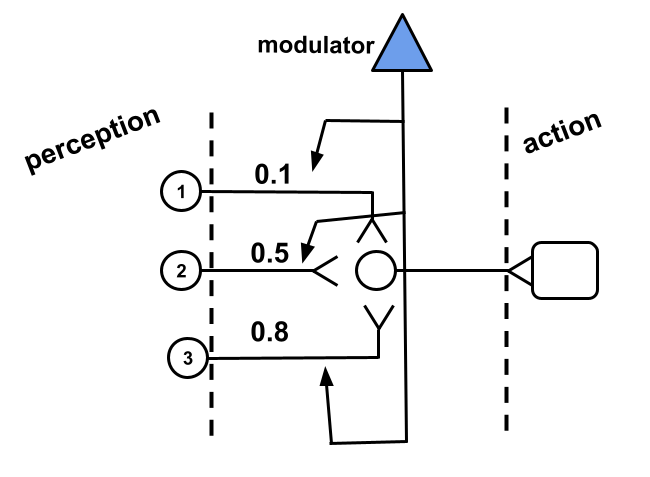

Let’s complete our understanding of neural systems by introducing a new element, that of the modulator whose task is to modulate the influence of one neuron over another. In Fig. 1 we show an example of how a modulator acts on the synapses of three neurons. The modulator would increase or decrease the influence that a particular synapse has over a postsynaptic neuron.

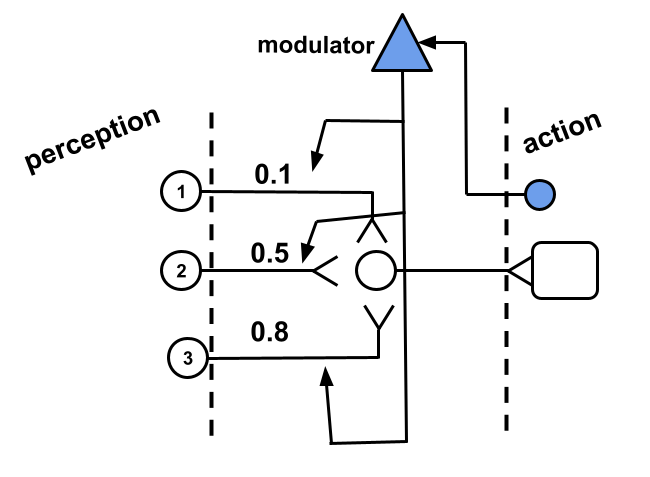

How would the modulator decide when to modulate? The modulator must have a input of some kind that triggers its action over the synapses of other neurons. In the best scenario, the activation of the modulator follows a rating that the system gives to an action recently performed. In other words, the system would possess some way to evaluate the effects of an action recently performed and modulate responsible synapses accordingly. Our modulator, therefore, would implement some perception mechanism close to the effector of the system, that is, close to its output as in Fig. 2.

There are a couple of assumptions that the last paragraph implies. Number one, that the system has a way to evaluate an action. This means that the system can tell actions that are beneficial from actions that are detrimental. Number two, the system has a way to tell which synapses were responsible for a particular action; this is what is known as the credit assignment problem. These assumptions are quite bold, and modern science has not been able to provide a complete answer to the questions implied by them. Here, we will start by keeping these assumptions and slowly progress to dissect them and propose solutions to them.

How would the system know if an action recently performed was beneficial or detrimental to it? Pleasure and pain are ways in which the nervous system might be implementing teaching signals by which the action of neurons are modulated. Thus, in Fig. 2 the sensorial component of our modulator could represent a pain receptor positioned close to where a muscle contracts.

What is pain in the qualia sense of the word? Here it doesn’t matter. What matters is that the activation of the modulator in Fig. 2 could be thought of a nociceptive signal that captures the noxious effect of a particular action which in turn will modulate the synapses in the presynaptic neighbourhood by -most conveniently- decreasing their influence over the motor neuron.

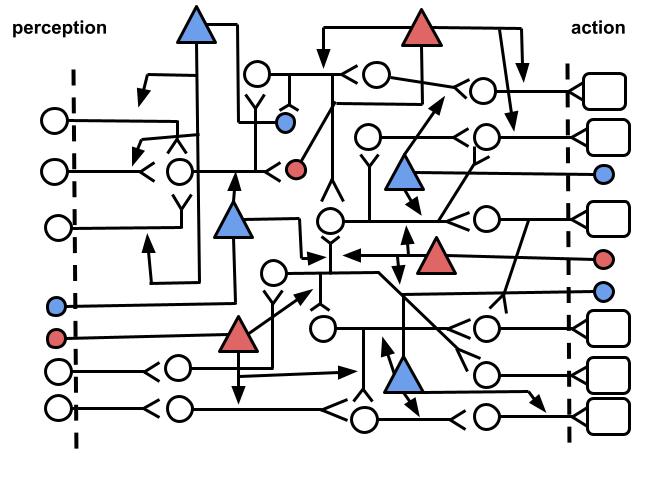

A modulator’s input component could also be located in other places within the system. For instance, it could be receiving activity from interneurons as shown in Fig. 3, where we have also differentiated between modulators that increase the influence of their targeted synapses (blue) and modulators that decrease them (red). The former could be read as the effect of an action that produces pleasure, whereas the latter could be interpreted as the effect of an action that produces pain1.

How it is decided where a modulator is located? In biological systems I would assume that genetics play a big role. Neural circuits have undergone an extensive process of trial and error throughout evolution. Additionally, my guess is that there is also some adaptive process that would modify the configuration of modulators within the system.

Our current knowledge of synaptic plasticity, that is, the capacity that neural systems have to modify their patterns of connectivity2 is based on the Hebbian adage of cells that fire together, wire together. This activity-dependent modulation assumes that a neuron is able to detect when another cell in its proximity is active concurrently. Several hypotheses of how this could occur have been proposed, and mechanisms such as retrosynaptic signaling have been observed to serve as a basis for synaptic modulation. Hebbian learning has been extended to capture the temporal dependence of firing patterns of neurons connected to each other. Spike timing dependent plasticity (STDP) has been put forward a strong candidate to explain how neurons modulate their activity.

How far can we get with Hebbian learning or a mechanism such as STDP? These two mechanisms lack the notion of a teaching signal that summarise the beneficial or detrimental effect of a particular pattern of activity of an assembly of neural cells. In contrast to backpropagation in machine learning, Hebbian learning doesn’t inform the system about the quality of performed actions. One could wonder why is it considered a strong candidate to explain the basis of memory and learning in neural systems.

Is there anything like our modulator in biological neural systems? At the time of writing there is no direct biological counterpart to the modulator described above. However anything like our modulator is biologically implausible until neuroscience discovers something like this. Let’s keep in mind that absence of evidence doesn’t imply evidence of absence. It could be the case that in the future a mechanism that directly modulates synapses is discovered.

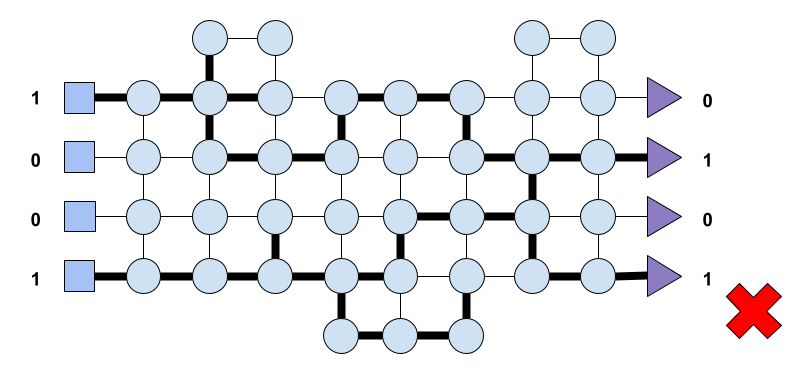

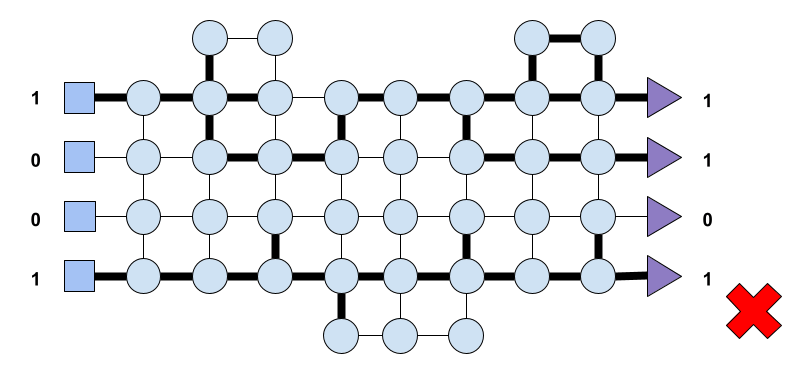

Learning is path finding. Let’s consider a network like the one shown in Fig. 4 where we present a simple network with input nodes represented by squares, processing nodes by circles and output nodes represented by triangles. The flow of information then is from left to right, and let’s say that as in previous cases to activate a neuron, that is a node, incoming activity needs to surpass a threshold.

Let’s say that the network receives as input the vector (1, 0, 0, 1) where 1 denotes neural activity and 0 lack of it. Now, let’s suppose that the network outputs the vector (0, 1, 0, 1) as shown in Fig. 5. Furthermore, let’s assume that following an evaluation process the network, the system, deems the output (0, 1, 0, 1) as bad. This could be as a result of an activation somewhere else in the system of a quote-unquote pain receptor or any other signal that sensed the output (0, 1, 0, 1) and considered it noxious to the system. Leaving aside the fact that biological neurons undergo a refractory period after activation (which leads to the credit assignment problem described above) we could say that the system should penalise those neurons that led to the undesired output. Such penalisation should be applied at the synapse level of the neurons involved, which resulted in the path that led to the aforementioned output.

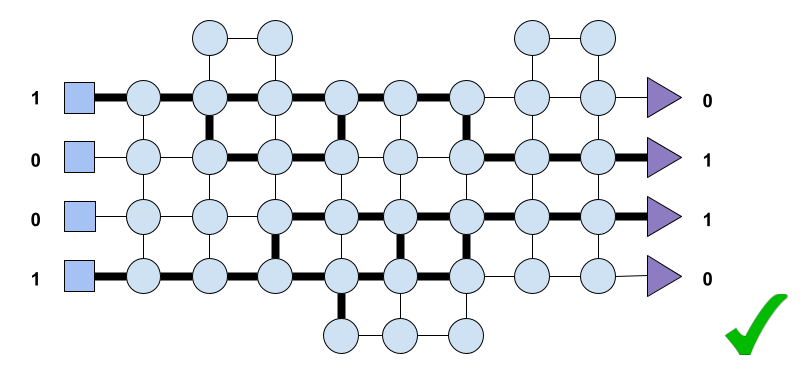

Let’s suppose that at another time the network receives the same input,

that is, input (1, 0, 0, 1), only that this time because of the status of each node at the time of input arrival the system yields the output (1, 1, 0, 1). In Fig. 6 we show the path that resulted in such output. Once again, the system must update the inter-node connectivity accordingly and penalise such connections that led to the undesired output. How does the system achieves that is not something we care for now. It could be that the system makes use of modulators as explained above or some type of Hebbian learning.

Let’s suppose once again that the network receives input (1, 0, 0, 1), and as a result of the inner dynamics of the nodes comprising the system, the output this time is (0, 1, 1, 0). Let’s imagine that this time the system deems such an output as beneficial for the system based on some evaluation process that we do not explain here. The nodes involved in such an activation trace a path shown in Fig. 7. This time the system must reward the nodes, the connections, that led to the observed output. The system must reward the path that led to it.

During our early years, our nervous system spent a considerable amount of time discovering paths. Paths from areas in the cortex to the muscles in our limbs. Paths that resulted in motor behaviour that prevented us from experiencing pain. Later, the brain also discovered paths within itself to and from areas associated with abstract thought.

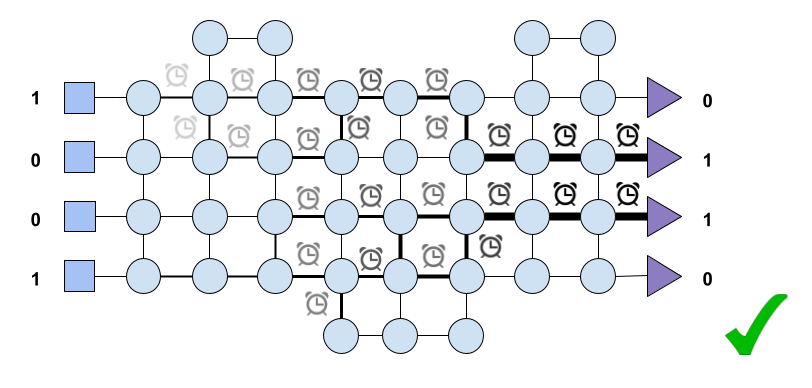

After the evaluation of a response the system must reward or penalise the connections that led to it. All well and good if the system came to a complete halt so that the system would know exactly what nodes, what connections to blame or to credit. This not only implies that the system is able to pause completely but also that it possesses global information regarding the state of each of its constituents and also that there is a global clock synchronising the action (or pause) of every node. This is the case of artificial neural networks and the backpropagation algorithm, but not the case of biological neural networks. Rather, the system has to rely on -or better said cope with- local information and asynchronicity of its constituents. Moreover, because neurons turn on and off, because they possess a refractory period, the picture looks more like in Fig. 8 where by the time the output units have been reached and the appropriate evaluation has occurred some nodes in the system might have undergone quiescence and thus the system is unable to assign the proper credit or blame. How do biological neurons solve such a conundrum is still a matter of much research and debate. If I was to speculate, I would say that, number one, the system implements credit (and blame) assignment all along the network and its intermediate steps, that is, not only when an output has been emitted. Number two, I am of the belief that neurons must make use of some sort of signalling molecule that stays in the extracellular medium after neural activation. This, by the way, is a potential explanation on how Hebbian plasticity might work [2].

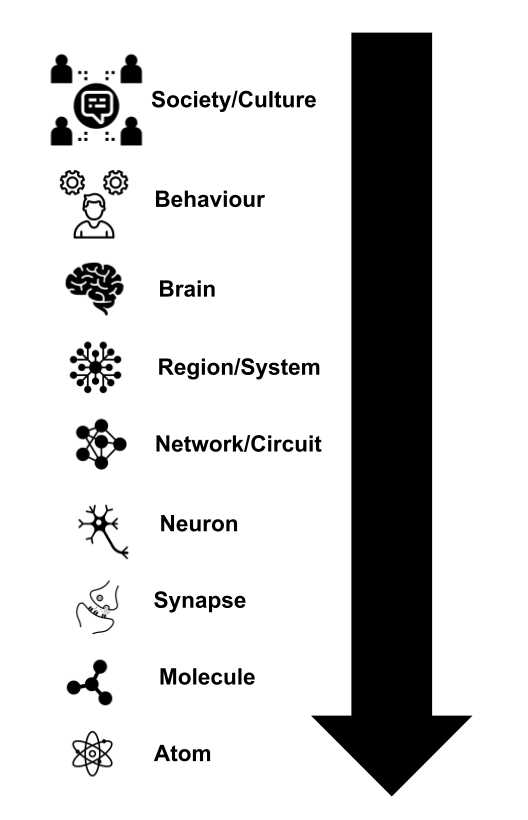

Take a look at Fig. 9 below, where we present the different levels of abstraction in which a neurological or psychological phenomenon can be studied.

One particular feature of our nervous system is that the teaching signal regarding how good or bad was a particular response seems to be occurring at different levels of abstraction. Neurons are relying on a reward/punish mechanism to modulate their connectivity at the level of individual neurons when for instance we are learning a new motor behaviour as in the case of learning to play an instrument, a martial art or some type of dance. But it also seems that the same mechanism is acting at a higher and more abstract level that goes beyond neuron pairs (as in pre- and postsynaptic cells). Think for instance the last time you said something you must not have said in a social situation like a dinner. I bet that the moment you realised that you should have not said what you said you kept ruminating in your mind the thing said and probably the reaction of people that listened to it. This rumination serves the purpose of you finding what was wrong in what you said and (everything surrounding the context) in order to avoid repeating such a situation in the future. In this example you, your mind, wants to assign blame to the particular wrong said thing. Such blame is not assigned at the neuron level, rather at the level of groups of neurons encoding for the said thing. I would not be surprised if one of the features that our brain possesses, which gave us an advantage over other species, is that of the recursive nature of credit/blame assignment which provides the system with a modulation mechanism at different levels of abstraction. This could be one of the core algorithms that the brain performs; this idea however remains to be explored.

- Above we said that at this point the question what constitutes pain or pleasure is not relevant. Stricto sensu, it is not that because of pain or pleasure a particular cell in the nervous system becomes active, rather it is the other way around: the activation of such particular cell is the pain or the pleasure itself, but we will come back to this question in a later Book. ↩︎

- Including the strength of their connections. ↩︎

References

[1] Eric R Kandel, James H Schwartz, Thomas M Jessell, Steven Siegelbaum, A James Hudspeth, Sarah Mack, et al. Principles of neural science, volume 4. McGraw-hill New York, 2000.

[2] Ami Citri and Robert C Malenka. Synaptic plasticity: multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(1):18–41, 2008.