“It’s more fun to compute”

– Kraftwerk

“Computer science is no more about computers than astronomy is about telescopes.”

– E. Dijkstra

“When I consider what people generally want in calculating, I found that it always is a number.”

– Al-Khwarizmi

“It is unworthy of excellent men to lose hours like slaves in the labour of calculation which could safely be relegated to anyone else if machines were used.”

– Gottfried W. Leibniz

“She’s smart, like a computer.”

– Morty Seinfeld in the Seinfeld episode “The Van Buren Boys“

Why compute? What needs do we have as a species for computation and why do we need to compute at all? Indeed we have been interested in computation since the dawn of civilisation, and it was not until recently that we as a species established the grounds in which to study the principles of computation formally. These were set up by Alan Turing and his doctoral advisor, Alonzo Church, during the first half of the 20th century.

Although a computer is a modern term which nowadays might trigger the visual imagery of a keyboard, a mouse1, a monitor, a laptop, etc. its notion goes back in time probably to the times of Babylonians and Ancient Greeks. One thing we need to understand is that the history of computation is not the same as the history of the computer. The former contains the latter.

Efficient arithmetic calculation and reckoning for the purposes of taxation, barter and land distribution were some of the earliest human activities that prompted our species to develop computational mechanisms, where perhaps the most rudimentary device -and still in use today- is the abacus.

Do you know how to multiply two 4-digit numbers, say for instance, 1359 and 2015? I’m sure you do. For that, you use an algorithm to be performed with pen and paper (better with a pencil, perhaps). Well, performing multiplications of large numbers motivated our ancestors to develop algorithms that could realise such operation in an efficient and reliable manner. This need also led us to ponder about the right representation of quantities. Let’s not forget that the Hindu-Arabic numeral system -the one we use today to perform arithmetic and that we learned in elementary school- was adopted by western civilisation only during the high Middle Ages. Prior to that time we made use of Roman numerals to represent numbers, a non-optimal choice to perform simple arithmetic computations. Back in those days one had to rely on instruments like the abacus to perform computations for trade and commerce. The introduction of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system in Europe was possible after the work of the Italian mathematician Leonardo de Pisa, a.k.a. Fibonacci, and by the translation of the work of Persian mathematician al-Khwarizmi2 between the 12th and 13th centuries.

One of the most important inventions in the history of our species is that of the positional numeral system to represent integers, that is, the numbers you can count with your hands (even if you need more than the pair you have). So much of an invention that Gauss, the prince of mathematics, was quoted once wondering what would it have been of mathematics, if Archimedes -one of the most important mathematicians of antiquity- would have used a positional representation system like the Hindu-Arabic numerals. Possibly mathematics -concluded Gauss- would have been advanced by hundreds of years. Too much speculation, but then again ancient Greeks were interested in geometry not in arithmetic, let alone algebra. A positional numeral system, like the Hindu-Arabic one, allowed for the development of techniques (today we call them algorithms, vide infra) to perform arithmetic calculations such as multiplication, division or the calculation of square roots, efficiently. In modern times, we learn such algorithms during our early school years. One example of such algorithms will have to be the one you would use to multiply the two 4-digit numbers mentioned above.

In addition to arithmetic calculations, prediction was also a reason why mankind was interested in computation in ancient times. In particular after arriving at a sophisticated level of abstraction in which to observe and study nature and its patterns. Having the ability to predict the occurrence of natural phenomena that are related to human affairs such as agriculture, seafaring, commerce and the like, required the capacity to perform computations. Our ancestors became aware of such a fact after inspecting the heavens with rigour. It is worth mentioning at this point what some researchers claim to be the earliest computing device in human history, namely, the Antikythera mechanism. Discovered in a shipwreck close to the island of Antikythera, Greece, this mechanical device was developed somewhere around the second century BCE for the purpose of predicting the motion of celestial bodies [1, 2, 3]. It is a perfect example of the level of sophistication that ancient engineers possessed when building mechanical devices.

More on prediction, there is also a famous anecdote regarding the pre-Socratic philosopher and mathematician, Thales of Miletus and his predictive powers. The anecdote tells that Thales was able to predict a good harvest of olives by observing patterns of the Mediterranean weather. After doing so, he acquired all the presses in Miletus for the production of olive oil. By renting them out to oil producers, he became a wealthy man; thus showing not only the benefits of studying nature, its patterns, and the importance of prediction, but also that philosophy is not in opposition with capitalistic endeavours.

Back on computation and its applications, some of these also include the storage and transmission of information, which resulted in a new means of communication (think for instance on the Internet and the apparition of the email). However, historically we only became aware of the potential of computation in telecommunication systems after the arrival of the first generation of electronic computers.

But how did this res machina to carry out computations come into existence? As one would have expected, the history of computation is tied together with the development of instruments to perform computations, which ultimately led to the creation of the electronic digital computer. Notice how I emphasised the quote-unquote full name of the computer. The computer that we all use and love today is electronic and is digital. These properties could be irrelevant for most people but they actually point to the fact that not all computing devices, i.e. computers were, are or can be, electronic nor digital. Modern computers, the type that most of us use today, are the result of a very particular paradigm of computation, one that uses electronic circuits implementing digital logic as its medium.

Before the rise of electronic digital computation there were different paradigms, different ideas and proposals regarding the right medium to perform automatic computations. Pre-electronic efforts used mechanical gears and a base 10 numeral system, akin to our counting system. These early computers were aimed to perform computations as simple as arithmetic calculations but also as complex as polynomial approximations to trigonometric and logarithmic functions, as I will describe below. Calculators like Pascal’s Pascaline and Leibniz’s stepped reckoner, both built in the 17th century, were examples of these early devices. The latter was able to perform the four elementary operations and received such a name because of the particular type of cylinder used throughout the device. Incidentally, from a certain point of view it can be said that the modern computer started with the work of Leibniz, but more on that later.

In the 18th century, the English polymath Charles Babbage, motivated by the observation of -human- errors in tables of logarithms, went on to design a mechanical computer, the Difference engine followed by another, the Analytical engine. The former was designed for the purpose of producing mathematical tables for logarithms and trigonometric functions via polynomial expansion, whereas the latter was envisioned to be a multi-purpose calculating device by reprogramming its configuration. However, neither of which saw the light of day in Babbage’s times3 due to a lack of funding. Nevertheless, some ideas in Babbage’s designs were later incorporated into electronic computers, namely, the use of storage to record the results of intermediate computations4, and probably most important, the idea of a general-purpose computation implemented in the designs of the Analytical engine.

Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace, better known as Ada Lovelace and the daughter of the Romantic poet Lord Byron, became involved deeply in the history of computation. A mathematician on her own account, she met Babbage during one of the intellectual soirées organized by the latter, where she heard all about his engines and became hooked right away. Ada Lovelace thought that the Analytical engine could be used not only for the purpose envisioned by Babagge, but also to write music, produce graphics and solve mathematical and scientific problems. (As a side note, much later, and perhaps motivated by some sort of Ada optimism, computer scientists came to think that computers are the right medium to implement human-level intelligence, see below.) Notoriously, Ada Lovelace translated a memoir by the Italian mathematician -and later prime minister- Luigi Menabrea on the work of Charles Babbage. In her translation she included supplementary notes where she described how the Analytical engine could be programmed, and provided examples of algorithms to perform several types of calculations. For this reason, she is regarded by some as the world’s first computer programmer.

Prior to Babbage’s ideas, mechanical computers were intended for a single purpose. Most of the time, arithmetic calculation. With the Analytical engine, Babbage goes beyond the idea of single-purpose computers to that of computers that can perform diverse functions based on a “program”, or set of instructions provided to the engine via punched cards, a method that was already in use in automatic looms. Punched cards came in two flavours, namely, one to represent operations and another one to represent data. This hints the idea of the stored-program computer and the modern microprocessor (vide infra). Because of this, the Analytical engine is considered the first modern computer. This notion of general-purpose computing is something that later, after the formal study of computation pioneered by Alan Turing and Alonzo Church, would be called universal computation.

As I mentioned a few paragraphs above, mathematics and physics were revolutionised after the adoption of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system. The same can be said of computation with the adoption of the binary number system, which with the development of electrical devices launched computer design into a new era. The binary number system is a system consisting of only 2 digits, namely 0 and 1, in contrast with the decimal number system which uses 10 digits (from 0 all the way to 9). We will see below that the dichotomical nature of the binary system can be mapped to electronics with the use of switches where 0 equals an off state and 1 an on state in an electronic circuit. This is the fundamental principle of electronic digital computation! Binary numbers allow arithmetic and electricity to be united [5].

I say that it all started with the work of Leibniz at the turn of the 17th century. He motivated the investigation on the use of the binary number system for philosophical enquiry inspired by the I Ching and eastern philosophy. However, his step reckoner, that is, the mechanical calculator that he invented, did not made use of this particular number system. He was unaware of a potential link between the binary number system and computing machines. However he advocated for the use of this number system to perform calculations and described how to do so in his Explication de l’arithmétique binaire written in 1703. The adoption of the binary number system in the development of computers would only occur after the observation that electronic switches used for relaying telephone lines could be used to perform simple arithmetic (see below).

The English mathematician George Boole, motivated by Leibniz’s work and his own desire to formulate a calculus of reason, devoted himself to the study of symbolic logic. In his (somewhat-ambitiously-titled) book The Laws of Thought he set up the principles of what later would be known as Boolean algebra. This describes the outcome of logical operations such as conjunction5 and disjunction6 over binary variables. Moreover, he argued that there exist mathematical laws to express the operation of reasoning in the human mind, and then showed how Aristotle’s syllogistic logic could be reduced to a set of algebraic equations. His work, further developed by mathematicians like Augustus de Morgan provided the foundations for computation based on the binary number system, which is the digital in digital computation, that is, computation that uses digits rather than continuous values. As mentioned above, in the case of computation based on the binary number system, the digits are 0 and 1. With the work of Boole, logic becomes arithmetic. His was a step towards performing calculations using logic gates. However, his work was mainly theoretical as he never built any kind of device.

The development of numerical methods to perform complex mathematical operations combined with the possibility of performing simple arithmetic operations using Boolean algebra paved the way for digital computation. A missing link concerned its implementation. This occurred by the observation that certain electronic devices -such as vacuum tubes- can act as switches, i.e. devices that toggle between 2 states. Here was the missing piece for the realisation of electronic digital computation. In this way, logic gates -the abstract components of Boolean algebra (vide supra)- were implemented using them. Such an observation was made by Claude Shannon, the father of information theory, in his master thesis. He was the first person to apply Boole’s logic into switching circuits and to see the connection between relays and Boolean operations. This allowed binary arithmetic and more complex mathematical operations to be performed by relay circuits because essentially a computer is a synthesis of Boolean algebra and electricity [5]. Actually, before Shannon’s master thesis, Boole’s algebra appeared to be of no use. In his thesis, Shannon also showed how the design of circuits and telephone routing switches could be simplified using Boole’s symbolic algebra.

War in the first half of the 20th century, the need to calculate ballistic trajectories and to encode and decode encrypted messages also motivated the creation of computers, which by then were either electromechanical, mechanical, or analogue. The term computer was inherited from the job that people -mostly women- carried out for the war effort7 by creating tables containing the results of simulated ballistic trajectories based on different environmental conditions, among other tasks of numerical nature. The first non-human computers were devices that occupied large rooms, consumed loads of energy, and were prone to calculation errors due to the nature of their components. Vacuum tubes, used for binary computation, generated a large amount of heat and had a very short lifespan, so they had to be replaced constantly to avoid mistakes in calculations [4, 6].

According to history, the award for the very first electronic digital computer goes to the ABC, the Atanasoff-Berry computer. Although the Z3, developed by the German engineer Konrad Zuse, precedes it by one year, it was not programmable and used the decimal number system. The ABC used the binary number system, it was fully electronic, and computation and memory were separated. It started operations in 1942. Around the same time, efforts from different groups around the world led to the creation of the first generation of computers, which include the ENIAC, the COLOSSUS, the Manchester Mark I, and the BOMBE -built by Turing to crack the ENIGMA code-, just to name a few. During the war period, some of the use of computers include deciphering the Lorenz and Enigma codes, calculating ballistic trajectories, and perhaps most importantly, running the simulations required to develop the atomic bomb. Later, when the world powers transitioned from the Second World War into the Cold War computers became essential for the simulations required to further develop atomic weapons, in particular for the creation of the hydrogen bomb [7], as well as managing air defence systems like the SAGE system in the US. In the context of using the computer to advance nuclear warfare, the work of one particular mathematician enters the story. And no, I’m not talking about the celebrated Alan Turing, but about John von Neumann (more on him below). However, not all computers had a somewhat bellicose purpose. Computers in this early era were also built to be used in administrative and business domains. One example is the UNIVAC (universal automatic computer), developed by a computer company founded by Eckert and Mauchly from ENIAC fame, which in 1952 predicted successfully the election of president Eisenhower using a 1% population sample. Around this time, it was not uncommon to hear laypeople and the press refer to computers as electronic brains, as if number crunching was the hallmark of brain operation or intelligence.

At this point in our story let’s ask ourselves what were the different paradigms of computation. That is, what have been the different proposals when it comes to the medium where to perform computations? Across human history, there have been different ideas and ways regarding how to carry out computations, i.e. calculations. Remember that our story begins more or less with the abacus and finishes on the laptop sitting in front of you. When considering the different paradigms of computation, these have been mechanical, electronic, digital, analogue, decimal, and binary8. Some of these are not mutually exclusive, so for instance, your laptop is an example of an electric digital binary computer, whereas Leibniz’s step-reckoner was mechanical digital and decimal. Analogue computation refers to computation where data and values are represented by physical quantities. Digital computation is the opposite of analogue computation, but it is not that digital computation uses non-physical quantities9 to represent numerical values. Rather, digital computation discretizes analogue quantities based on a predefined strategy in order to represent them using digits, that is, integer values. (In the case of our modern electronic computers, anything below 5 volts is considered an off state, i.e. 0, and anything above that is an on state, or 1.) Mechanical is in contrast with electronic as a concept. The latter involves the use of voltages, currents, resistances, and everything related to the flow of electrons through a conductive material to realise some type of work. The former doesn’t, and often involves gears and a source of energy different than that of electricity to carry out work.

Electronic digital computers, that is, computers that use electronic components that represent numerical values as digits, proved to be more efficient, reliable and more portable than their mechanical and analogue counterparts. When considering electronic digital computation, there is a paradigm or architecture that stands out, and even bears the name of a person, the Hungarian mathematician John von Neumann10.

The history of computation has its heroes and its champions. Perhaps the most renowned is British mathematician Alan Turing. John von Neumann, one of the most important scientists of the first half of the 20th century, is a figure from whom we hear very little in pop culture. Along with Alan Turing, he is quoted as being one of the fathers of computer science, but unlike Alan Turing he is fairly known. Perhaps because he lived a quote-unquote more conventional life11. However, von Neumann and his colleagues did an important contribution to the development of the modern computer.

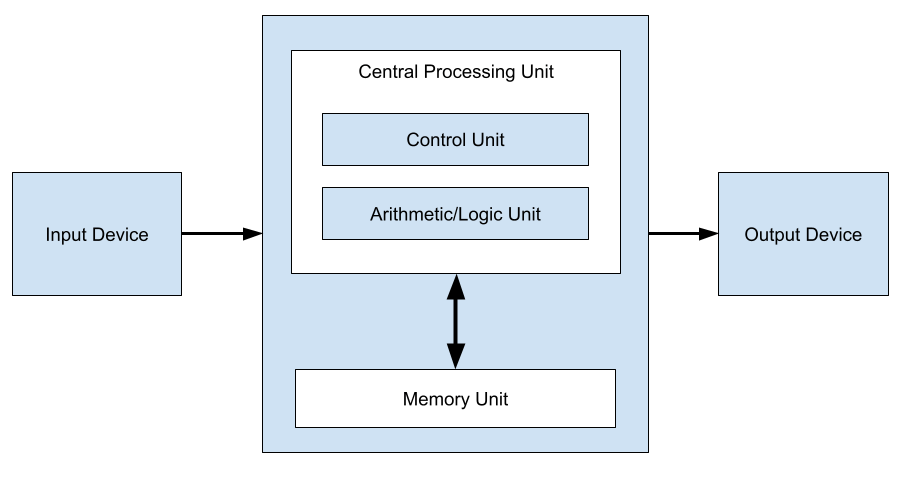

In a document written in 1945, now known as the First Draft, von Neumann laid out the principles of what now is called the Von Neumann architecture (or VN architecture for short) In this architecture, there is a central processing unit responsible of performing computations to data coming from memory via a bus, which is a technical term for a data channel. Also there is a control unit keeping track of the instructions to be carried out by the processing unit over the data. There is also external mass storage and mechanisms to handle input and output. However, perhaps the most important feature of such an architecture is the idea of the stored-program, which means having both program instructions and data residing in memory. Prior to this idea, computers had fixed programs, and if someone would like it to perform another type of operation, the computer would need to be reprogrammed. This implied rewiring the whole system or even redesign it. Fig. 1 shows an schematic of the VN architecture. As described, the bus is shared by program and data, which is in part responsible for the so-called Von Neumann bottleneck, but more on that in a future post.

So popular this architecture became that today conventional computers follow its principles with the idea of a re-programmable computer where the program resides in the computer’s memory along with its data12, which means that the computer can be a word-processor, a spreadsheet and a videogame, just to name a few examples, without changing its physical components.

Nevertheless, von Neumann and every other computer designer back then had still to face the issues of faulty electronic components, such as the short lifespan of vacuum tubes, along with a considerable amount of energy consumption. For instance, the ENIAC, one of the first computers ever developed, comprised 18 thousand vacuum tubes, consumed 150 kilowatts of electricity, and required air conditioning for cooling. Its longest running period without failure was five days [4].

The next revolution in computation was related to materials science and the invention of the transistor which is a semiconductor device that replaced the vacuum tube. In essence, it still acts as an electronic switch, and logic gates can be created using them. It was invented by physicists John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley in the 1950s who had the goal of inventing a more resilient alternative to the vacuum tube. Transistors were smaller compared to vacuum tubes and consumed much less power. The second generation of computers used transistors instead of vacuum tubes. Because of this, new computers were smaller, faster and more reliable than their predecessors. In 1958 appeared the first commercial computer based on transistors, the IBM 7090.

Despite the fact that the use of transistors made the construction of computers somewhat easier, computer makers still had to face one problem: that of wiring together all the components. Manual assembly of a large number of components often led to faulty connections. The observation that the material from which transistors were build could also work to make all other components, like resistors, capacitors, etc. led in the 1960s Jack Kilby from Texas Instruments to invent the integrated circuit (IC). An IC is a single piece of electronics containing all the elements required for digital computation. Jack Kilby made his using germanium, a semiconductor material; but around the same time, Robert Noyce, co-founder of the tech company Intel, built his out of silicon. His design proved to be more efficient to build at scale, and so the first seed for the personal computer was sown along household names like that of Intel and Silicon Valley.

An IC is significantly smaller than a circuit comprising the same components in an independent fashion. Nowadays, ICs are extremely small and they pack billions of transistors. The width of conducting lines among components is usually used to keep track on the progress of the technology. Today, it is measured in tens of nanometres. This fact has led to the observation that if the transportation industry kept pace with the computer industry today we could travel from New York to London in a second for cost of only a penny [9]. Kilby and people at Texas Instruments commercialized the IC by creating a hand-held calculator that was as powerful as the existing large, electromechanical models.

One fine day the Japanese company Busicom, manufacturer of calculating devices, requested Intel to design an IC for their new line of programmable calculators. Intel, which by then was dedicated to the production of electronic memory, in particular, RAM ICs, came with a design of a single chip that contained all the ingredients of a CPU. This was the birth of the microprocessor. A microprocessor is an IC that condenses all the notions of a computer à la von Neumann in a single chip. Its creation set the stage for the personal computer, and thus for the smart-phone era. The microprocessor led to the availability of low cost personal computers. However, there were skeptics around the idea of the home computer. Famous among them is Ken Olsen, former CEO of the now-defunct IT company DEC, who is remembered -among other things- for saying that “there is no need for any individual to have a computer in his home” (quoted in [4]).

In 1974 the Intel 8080 chip appeared. It was the first general purpose 8 bit microprocessor13. Soon after, IBM started using Intel chips to build their computers, which by then became personal. Just a few years before, Moore’s law was stated. This law rather than a physical one is more of an observation. The observation made by Gordon Moore, another Intel co-founder, was that every two years or so the number of transistors in a chip doubled, and as a consequence, the number of calculations that a microprocessor can perform also doubled. This observation has hold since the 1970s, but microprocessor manufacturers are not certain until when it will do so. In recent decades, Moore’s law has acted more as a goal or an agenda than an observation; a law that points in the direction that chip manufacturers should focus their efforts on. Some claim that the progress has slowed down since around 2010. One thing is certain, the amount of miniaturisation in transistor technology will soon reach atomic limits and with it all the undesired consequences of dealing in the quantum realm. Possibly, before reaching such a limit, manufacturers will have to deal with yet another undesired consequence of packing so many transistors in a small area, namely, heat. Lastly, another consequence of keeping up with Moore’s law is the negative environmental impact that sourcing the raw materials for chipmaking has on the planet [10]. It seems that we are reaching the limits of the physical medium where to perform computations à la von Neumann. Are there any alternatives? In a future post, I will explore this question.

Isn’t it impressive that we have laptops and smart-phones? Could you imagine living in a world where this kind of devices never came into existence? Microprocessors are at the center of a computer’s CPU, or rather said, they are the CPU. They allow us to do all the calculations that since the advent of computation the human race has been interested in, what Leibniz and von Neumann dreamed of, and much more. And let’s not forget that most microprocessors follow the principles of the VN architecture. All modern information technology is based on them. From the computer you use to stream a movie from the Internet, to the servers behind an e-commerce retailer. So, every time that we are working on our computers or looking at our smartphones, we tip our hats to good ol’ John von N. and colleagues. The VN architecture is where we have been performing our computation since the advent of personal computing. This is also the paradigm where we have carried out all our efforts regarding artificial intelligence (AI). Naturally, GPUs are used extensively in AI, mainly when it comes to machine learning. GPUs don’t follow the VN principles per se. Rather it is a different type of architecture optimized to carry out parallel computations of simple(r) arithmetic operations. This specialized computing device is a component of a system which still falls within the VN sphere. It wouldn’t be so, if say the GPU did all the operations required in a machine learning scenario, that is, if it behaved more like a general-purpose computer, but then it would lose its raison d’etre.

So, at this point it is a fair question to ask whether the VN architecture is the right paradigm for AI. Why are we using this paradigm in our efforts to create intelligent machines? Is it because it was the paradigm already in use and all others would imply an uncertain research path? Is using this paradigm for AI the lowest-hanging fruit? What reasons do we have to think that the modern computer is the right medium in which to create machines that exhibit human-level intelligence? Or to put it in another way, what reasons do we have to think that we can endow the modern computer with intelligence? What reasons to think that a digital system following the principles of the VN architecture has enough capacity to “house” this form of intelligence? Why our modern computers and not Babbage’s Analytical Engine? Or Leibniz’s step reckoner? Or the steam engine? This is the topic that I will explore in a future post.

Lastly, it is funny to anthropomorphize14 the computer and call them smart just because they are good at performing arithmetic calculations. Perhaps performing arithmetic computations is one of the simplest things to do, as it follows quote-unquote simple rules, that is, they are algorithmic, whereas something like balancing our bodies when going up and down a staircase or the so-called common sense are examples of something that looks less algorithmic, and thus more complex to implement in a mechanical or electronic device. Would the implementation of those behaviors require that we go beyond VN architectures?

References

[1] Tony Freeth, Yanis Bitsakis, Xenophon Moussas, John H Seiradakis, Agamemnon Tselikas, Helen Mangou, Mary Zafeiropoulou, Roger Hadland, David Bate, Andrew Ramsey, et al. Decoding the ancient greek astronomical calculator known as the antikythera mechanism. Nature, 444(7119):587–591, 2006.

[2] J. H. Seiradakis and M. G. Edmunds. Our current knowledge of the antikythera mechanism. Nature Astronomy, 2(1):35–42, January 2018.

[3] M. T. Wright. The antikythera mechanism reconsidered. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 32(1):27–43, March 2007.

[4] Gerard O’Regan. A brief history of computing. Springer, 2008.

[5] Charles Petzold. Code: The hidden language of computer hardware and software. Microsoft Press, 2000.

[6] Doron Swade. The history of computing: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press, 2022.

[7] Ananyo Bhattacharya. The man from the future: The visionary life of John von Neumann. Penguin UK, 2021.

[8] Leonard M Adleman. Computing with DNA. Scientific American, 279(2):54–61, 1998.

[9] David A Patterson and John L Hennessy. Computer organization and design: the hardware/software interface 5th ed. Elsevier, 2014.

[10] Kate Crawford. The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary

Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press, 2021.

- That is, the electronic device, and not the rodent. ↩︎

- To whom we owe the term algorithm. ↩︎

- In 1853, George and Edward Schuetz built the first working Difference engine in Sweden based on Babbage’s blueprints. The machine worked as planned printing mathematical tables. It showed the potential of mechanical computers as tools for science and engineering [4]. ↩︎

- What we now know as computer memory. ↩︎

- Logical and. ↩︎

- Logical or. ↩︎

- And long before that. In the past when someone wanted to publish a set of mathematical tables, they would hire a bunch of computers, that is, people that carry out calculations for hire, set them working and then collect the results [5]. ↩︎

- Nowadays we even have molecular [8] and quantum paradigms. ↩︎

- Something like Descartes’s res cogitans could come to mind, literally. ↩︎

- Not without controversy, because as it is with everything in history, no major invention is the work of a single person but that of a group of people working at different periods of time. The case of the so-called Von Neumann architecture is not different. If anything, it can be said that the Von Neumann architecture was the idea of at least 3 people: von Neumann himself, but also the engineers J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly, who designed and developed the ENIAC computer years before von Neumann considered electronic computation seriously. ↩︎

- It would look like when you’re a scientist that helped defeat Nazi Germany by breaking the code of the Enigma computer, Hollywood might be winking at you. Nevertheless, looks like von Neumann also lived quite an exciting life. To hear more about it check out this biography of him: [7] ↩︎

- Alternative paradigms used different locations to store program and data, as it is the case with the Harvard architecture. ↩︎

- An excellent and thorough dissection of how this chip works along with an explanation of how computers work can be found in [5]. ↩︎

- Like in the Seinfeld’s quote at the start of this post. ↩︎