“Having a thought does not mean having an internal

representation that is a cleaned up version of the

sentence any more than perceiving a red square

involves having a red square in the head.”

~Geoff Hinton.“But what then am I? A thing that thinks.

What is that? A thing that doubts, understands,

affirms, denies, is willing, is unwilling, and also

imagines and has sensory perceptions.”

~René Descartes.

What is a thought? Is it physical? Is it divisible? If so, what are its constituents? Where does it occur? What is its locus? Before we get into a cartesian debate about the distinctions between the res cogitans (the stuff of the mind) and the res extensa (the stuff of physical bodies) let’s take a step back and ask ourselves what is it to define something? What do we expect from a definition? What do we mean when we ask “What is X”? And only after we have answered questions as such we have the right to ask stuff like “What is a thought? What is thinking?”.

What is to define something? The answer: it is to associate a word, a term, to known concepts. Take for example the question “What is a kwyjibo?”. My guess is that the reader hasn’t heard the word kwyjibo before, and thus has no idea of what it might refer to. An answer like “It is a north american ape with bad temper” would give her a clearer idea of what it’s meant by that word (watch a kwyjibo here: https://youtu.be/HMGWCSVRAzo). That’s a definition!

However, there are times in which the question “What is X?” has the purpose of explaining the causes that give rise to X. Take for example the question “What is consciousness?”; unless you’re new to the English language -or to any language- when you ask such a question you already have an idea of what is meant by the word consciousness (it’s part of popular knowledge which means that its meaning is provided by its use in everyday life through a natural process of inference), therefore what you’re asking it’s not to associate that word to known concepts but to describe its causes in terms of -say- neural states or patterns of activation of cells in the brain or -if the reader finds it suitable- in terms of apples and oranges.

In sum, in common language there are two intentions to the utterance of a question of the form “What is X?”, to wit, Type I asks for the description of X in terms known to the person asking the question, whereas Type II asks for the causes or descriptions of X in terms of Y. Therefore, when we encounter questions in the (neuro)scientific or philosophical literature like “What is a thought? What is thinking?”, neither writer nor reader are asking such questions in the sense of Type I questions, for both writer and reader possess an intuition of what it is meant by words like thought and thinking. An answer to the question “What is a thought?” in the sense of Type I questions can be found in a dictionary for the English language; for instance, the Oxford Dictionary gives the following definition of thought:

An idea or opinion produced by thinking, or occurring suddenly in the mind.

Thus, when I ask here “What is a thought? What is thinking?” I appeal to questions of Type II. However, the question that rises next is what are the terms in which I look for a description of thoughts and thinking. What about the following options? “What is a thought in terms of neural activity within the brain?”, “What is thinking in terms of mental concepts?”, or “What is a thought in terms of blood flow within the neocortex?”. In this particular essay, I opt for the following kind of question: “What are thoughts (and thus thinking, vide infra) in terms of concepts within the mind?”. In the present essay I argue that thoughts (when described in terms of concatenation of symbols or concepts within the mind) come in two flavors: grammatical and symbolic (or primitive) thoughts.

Naturally, if we agreed to define a thought as a concatenation of concepts within the mind, we would need to further define what we understand by the term “concept”, and even by “mind”. Terms like “concept”, “mind” and “meaning” are tightly intertwined, and they will be the subject of a future essay. For the current discussion I appeal to the reader’s understanding of such terms, hoping that for the most part our notions of such concepts coincide. Now back to the distinction between grammatical and symbolic thoughts.

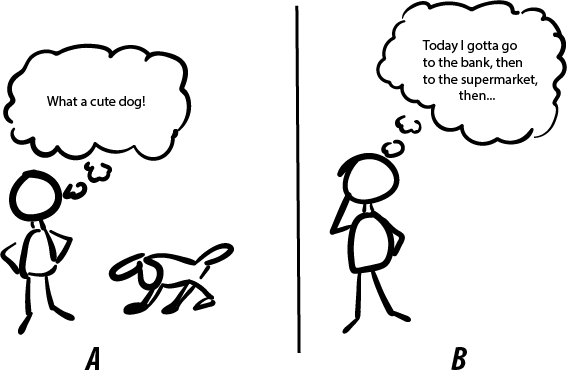

By grammatical thoughts I mean the kind of thoughts that we generally describe as an “internal dialog”, in which we follow the syntactic rules of our mother tongue’s grammar, i.e. thoughts that possess a grammatical structure identical to the one used in (but not limited to) oral language. We hear this kind of thoughts within ourselves as a result of much of our mental activity; for instance, we hear that inner voice (which surprisingly doesn’t possess a particular vocal timbre) whenever we identify something in our perceptual landscape (Fig. 1A below) or when we elaborate plans (Fig. 1B). This kind of thoughts usually precede the action of articulating language orally; in other words, we experience this inner dialog prior to speaking. (As I have argued previously, I’m aware that not all dialectic language is based on oral and hearing principles. Deaf people communicate through hand signs that depend on the visual capabilities of the interlocutor, and therefore the grammatical thoughts occurring in that particular type of people take the form of their particular dialectic system. People with hearing impairments are able to think in hand-gestures, that is, their inner language take the form of this particular form of communication.)

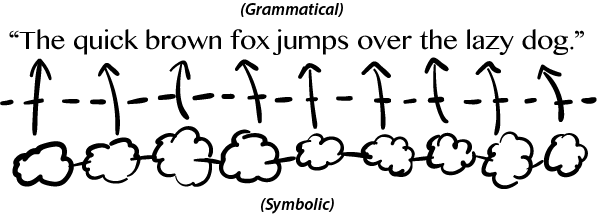

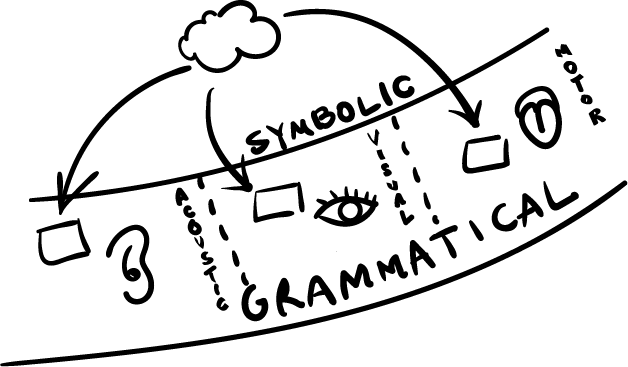

Grammatical thoughts are the tip of an iceberg, they are the culmination of a mental process. They associate a more primitive form of mental language (see below) with a mental entity that has the property of being articulated via motor commands (by the hand when written or by the vocal system when articulated orally) or perceived by a sensory system (by the eye or by the ear). Grammatical thoughts act in representation of a pure symbolic form of meaning within the mind. In other words, a grammatical thought is a “mask” worn by a more primeval mental entity. (Fig. 2A) Grammatical thoughts are composed of words as used in common language which are categorized as nouns, verbs, adjectives, and so on; and are usually articulated orally and parsed in an auditory fashion or visually in the case of written language (Fig. 3, top).

Not all thoughts are grammatical. The mental entities for which grammatical thoughts act as masks, that is, as representations, are symbolic thoughts, which I alternatively call primitive thoughts, and unlike grammatical thoughts, this type of thoughts are not constrained by the grammar we use in oral language, but might possess a grammatical structure of their own. Symbolic thoughts are blobs of meaning residing in an abstract space within the mind. They constitute a mental language in its own right, that elsewhere has been called mentalese, and predates the more elaborate form of grammatical language that we use everyday. Language, as we use it commonly, sits on top of this primitive/symbolic language system (Fig. 3). We know the concept of -say- “dog” before actually being able to name it, that is, to use it within a language. The words “dog”, “perro”, “chien”, etc. are just instances of a particular language system that we place on top of the symbolic notion of “dog”.

Symbolic thoughts are the currency of the mind. They are referenced and used in diverse brain regions for purposes that can be categorized as passive and active tasks. Passive tasks refer to sensory actions, which involve the action of parsing and identifying incoming stimuli to the senses; whereas active tasks refer to motor commands that set muscles in motion. Examples of passive tasks are the contemplation of objects in our sensory landscape (the screen in front of me, the taste of coffee in my mouth, etc.); whereas examples of active tasks are the motion of the larynx and tongue (among other organs) for oral communication, or the muscles in the wrist (among others) for written communication. Symbolic thoughts are the elements that take part in the computations of passive and active tasks in the same way as elements in the set of real numbers take part in mathematical operations. Moreover, symbolic thoughts are instantiated somewhere in between the centers for sensory processing and the centers for motor-command planning; and they are produced as a result of the processing of sensory stimuli or as a result of their own computations (Fig. 4).

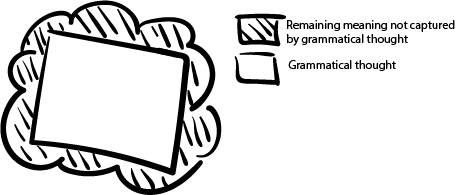

Furthermore, symbolic thoughts possess a richer content of meaning than grammatical thoughts, which usually constrain, limit or trim their meaning in order to make them fit within a particular set of grammatical rules. We see this happening whenever we are unable to remember a word for which its meaning is already in our mind: the tip-of-my-tongue phenomenon. Here, we perceive the presence of the symbolic thought but we are unable to trigger the generation of its correspondent grammatical thought and subsequent oral utterance. When perceiving the presence of such symbolic thought within our mind, we are actually feeling a blob full of meaning; but then, some of this meaning is lost when it gets constrained to a particular grammar in order to give rise to a grammatical thought. This is the reason why untranslatable elements from one language to another exist, and also why we sometimes have the feeling that a word in a particular language doesn’t encapsulate completely an idea or meaning that we might come across with, and the reason therefore why we create new words in a language.

Lastly, thinking is just the act of forming, creating thoughts. Thinking isn’t always the inner dialog following precise grammatical rules within a subject’s mother tongue; this is what I have been arguing above. Say, for instance, that you’re sitting in a table where close to you is a glass full of water; imagine that in a quick arm move you hit the glass of water with your elbow. A thing so simple as thinking that the glass is about to fall bypasses the grammatical generating/parsing process that occurs in the brain. This thought occurs in a fraction of a second and relies in a more primitive, symbolic communication form within the brain; and, as I will argue in following posts, constitutes the basis of intelligence because not only we think -symbolically- in words or objects of auditory nature but also we think -symbolically- in images and motion, that is objects of visual and motor nature, respectively.

Felix Cohen in 1929 published a paper [Cohen, F. S., “What is a question?,” The Monist, 1929, Vol. 39, pp. 350–364] that described the glaring omission from logic of a Boolean Algebra of questions on par and complementary to standard Boolean Algebra. In 1978 Richard Cox published a paper wherein he derives an algebra of questions (5. Cox, R. T., “Of Inference and Inquiry, An Essay in Inductive Logic” in Proc. Maximum Entropy Formalism, first maximized entropy workshop held at MIT) It took me some time to understand it bit now see it crucial to the develop of AI. My research has focused on trying what all this means in the development of intelligent systems and processes and have come to understand that intelligence is physical based on basic statistical mechanical principals. Last year I summarized my research on a paper in Entropy magazine titled “Physical Intelligence and Thermodynamic Computing” http://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/19/3/107

LikeLike

Thanks for the references, Robert. I will read your paper in the following days. Cheers!

LikeLike