I am currently working in a project that involves some sort of text mining and natural language processing (NLP). For this I need to disambiguate words and -if possible- relate them to their concept, that is, to their abstract pure form. One key requirement of the system that I am developing is its ability to map terms like “cortices” or “cortical” to the concept, or at least to their core word: “cortex”. I am aware that there exist techniques in NLP such as lemmatization and word-stemming with very good implementations in libraries such as NLTK in Python for this kind of tasks, but in my humble opinion these are artificial techniques that could potentially lead to writing very long lists of exceptions inside a script (actually, depending on the stemmer, NTLK would return “cortic” or “cortex” as the stem of “cortices”). Moreover, when it comes to artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), it has always been my intention to imitate nature and to stay as close as possible to the way natural intelligence works in order to reverse-engineer the processes that lead to a particular -and most of the time under appreciated- behavior.

So, for the purposes of the system that I’m currently developing, it would be necessary to have an algorithm that allows a computer to discover concepts from text, or at least, it’s able to map words to their canonical form (e.g. “cortical” and “cortices” map to “cortex”) in the most natural way without having to write long lists of word exceptions as a consequence of our poor understanding of language processing. I’ve experimented using modern NLP techniques such as word2vec, skip-thought vectors and other algorithms in the same lines. With these, I’ve achieved moderate amount of success depending on the dataset used during the training process. However, the occasion allowed me to reflect upon some aspects of language and knowledge acquisition which are the topics of this essay.

My first observation while using the word2vec algorithm is that during the process of word encoding the semantic value captured by the word’s morphology (in terms of the string of characters that make a particular word) is lost when going from words to binary vectors. In the case of the one-hot encoding used in word2vec a word becomes a binary vector of the size of the vocabulary used to train the algorithm (something that has to be predetermined ex ante leaving no room for modifications during the system’s runtime). Yes, I claim that already a word’s shape encapsulates certain semantic value because words that look the same most of the time have similar meaning. We come to appreciate such a fact when learning a new language, and trying to find our way through novel words and new ways to combine them and inflect them. Thus, in an algorithm like word2vec, the morphology of words is discarded completely, and the discovery of relationships among these (which exist in the every-day use of language) is left to the discovery of statistical patterns of co-occurrence within a given dataset.

What kind of relationships exist among words that are already present in their morphology? If we forget for a while that we are already proficient in the English language but on the contrary we were still finding our way through it and suddenly we came across words like “cortical”, “cortices”, “cortex”, etc. we would suspect that these words refer to a common word or concept simply because these words look similar. Moreover, we could even think that a word such as “cortazar” is also related to them, which is not the case. (Cortazar is the surname of a popular Argentinian writer.)

This observation had me thinking on some of the primeval movements that human reason performs on the myriad of stimuli entering the mind (or the brain, depending on what side of subjectivity you are watching from), which lie at the foundations of knowledge and language. Reason maps similar inputs to similar mental representations, and thus to similar outputs which ultimately yields to behavior. This latter fact should makes us appreciate one feature of reason that we usually take for granted, and which stems from the economical nature of human thought, to wit: the fact that words that looks similar will also sound similar and will refer to similar concepts. Stand there for a minute and think what would it be if the opposite occurred. Imagine for a second that the plural of the word “dog” is not “dogs” but “gersdis” (I came with this word by typing randomly on the keyboard!). Imagine as well that even though the plural of “dog” is “dogs” both words are pronounced differently. Here, the reader can argue that the latter example is impossible after we have agreed on the sound of the characters in the alphabet. However, coming to the English language from the Spanish language, I found that the pronunciation of words in English depends on the characters making up the word, for instance the words “sugar” and “suit” both share the bigram “su-“, but in each case it is pronounced differently. (Moreover, the word “gheess” should sound like the word “fish”, if we considered “gh-” as in “enough”, “-ee-” as in “halloween”, and “-ss” as in “tissue”.) In the same sense but in an extreme case I could ask you to imagine that the utterance of the words “dog” and “dogs” have absolutely nothing in common. Human reason is mostly about achieving more with less effort, that is, being economical; and thus we came up with a language system in which words that look the same, sound -in most cases- the same, and refer -in most cases- to similar notions. All of this, by the way, is lost with encodings and representations such as the one-hot encoding of modern NLP algorithms for ML.

I will take the case for morphology even further by proposing a new language based on the following alphabet:

Imagine that you observe words built from this alphabet for which you know almost nothing in advance. Almost immediately, an important aspect of language-parsing comes to mind; an aspect that we rarely think about, namely the importance of the blank space as word delimiter. Otherwise, how would we know when a word ends and another begins? I’m tempted to say that for reason the absence of input is as important as its presence. In other words, blank spaces, pauses and silences are as meaningful as are characters and sounds. (By the way, the use of the blank space in written text was not introduced in the Latin alphabet until roughly 600–800 CE. Before that it was even harder to read Latin texts; not to mention to discover their meaning without prior knowledge of the language.) Therefore, the reader’s first task when presented with a text comprising words from this new alphabet would be to know when does a word begin and where does it end. However, in order not to complicate things, I will make use of the blank space as word delimiter. Also, the direction of parsing (aka. reading) is from left to right as in English. (The importance of the blank space as well as the direction of language are two seemingly trivial aspects of language that we usually take for granted, except when confronted with languages like Chinese, where blank space is not used, or Arabic, where characters are read from right to left.)

If the reader came across words made up with the characters of the alphabet described above, and was asked to guess the meaning or the function of the words (in terms of their part of speech: verbs, nouns, adjectives, etc.) the best she can (think of trying to decipher the Voynich manuscript), she would carry out almost unconsciously the following actions, which lie at the core of -human?- reason.

- Identifying the null stimulus, and assigning it a value similar to other stimuli.

- Predicting incoming stimulus in the sequence.

- Assigning similar value to prediction errors as to prediction hits.

- Clustering morphologically similar inputs.

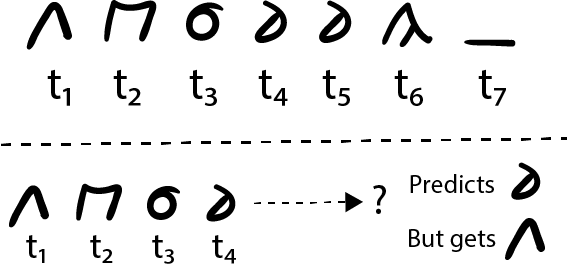

Consider the top part of Fig. 1 above. At different times you read each of the six characters making up the word therein. At the seventh time (t_7) you observe the blank space (the null stimulus) and that prompts you to consider the recently observed characters as a single word. Now let’s suppose that I present to you the same word once again, and then once more, and after that one more time… After a few presentations of the same word you will probably be able to predict the upcoming character when presented with the word character by character. (A particular feature of reason whether human or nonhuman is that most learning occurs within sequences. Maybe because the world and its phenomena occurs in time.)

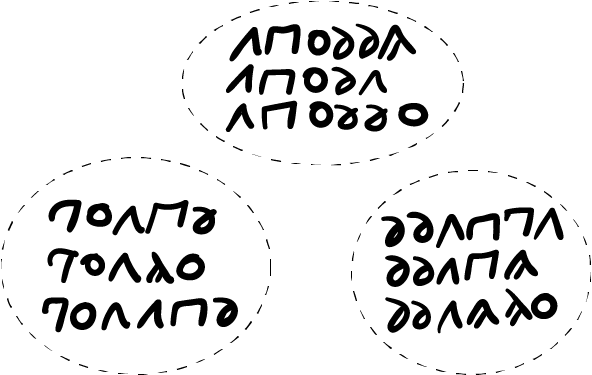

If I presented you now with a fragment of the word as in the bottom part of Fig. 1 above, at time t_4 you would predict that the upcoming character is the one that looks like a reflected “6”. Let’s suppose that this time you’re wrong, and in fact the next character I present to you is the one that looks like an “A” without the middle line. Here something essential to the operations of reason occurs next: instead of discarding the novel stimulus, reason receives it attentively until receiving the next null stimulus, i.e. the blank space. Once this occurs, reason clusters the mental (or neural, depending on what side of objectivity you are watching from) representation of the novel stimulus close to the one we observed before simply because both possess similar morphology. This a primal movement of reason, one that we perform unconsciously at every level of our mental/neural substrate as novel stimuli arrive from the senses. Thus, after being presented with different words from the alphabet above, we end up with clusters of morphologically similar words (or stimuli) like the ones in Fig. 2 below.

A feature that makes such clustering possible is that reason values mistakes, that is, prediction errors, as much as prediction hits. To the best of my knowledge, this doesn’t have equal in any ML algorithm. Actually, the outlook is quite the opposite: errors are discarded or are only appreciated for the information they provide regarding the difference between prediction/expectation and ground truth, but not for the morphological similarity that the current input has with previous observations, which as I have been argued possesses semantic value.

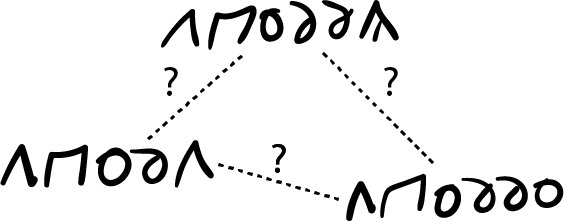

The next movement of reason consists in elucidating the possible relationships -if any- among the words or representations comprising each cluster. For instance, what are the relationships among the words in Fig. 3 below which belong to one of the clusters presented in Fig. 2.

For this task, reason requires vast observations (or in ML terms: massive amounts of data) in order to reveal how these words are used within a corpus, which basically implies that we would be relying on the discovery of statistical patterns of use of the words within a text. In other words, in this stage careful attention is paid to the co-occurrence of groups of words, and based on that reason is able to elucidate the role/function of a particular word in the current language. Here, the problem is reminiscent of the strategies used by modern NLP algorithms such as word2vec in which the algorithm discovers relationships among terms based on their statistics within a particular corpus.

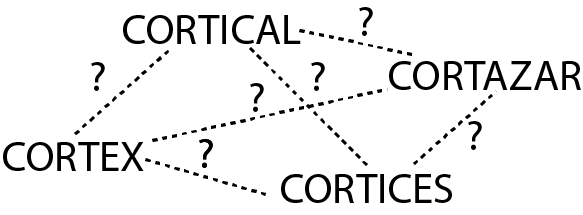

Now, let’s imagine that we know nothing about English. (But in a meta-space we are able to read this text though.) Let’s suppose that, similarly to Fig. 3 above, we were able to cluster some words we found in a text as in Fig. 4 below. Nevertheless, we don’t know anything about them: we don’t know what they mean nor what is their role within the English language (i.e. are they verbs, nouns, etc?). All we have done so far is cluster them -in our mind- based on their morphological similarity.

How could we discover the relationships among the words in Figs. 3 and 4, and the function of each one of them within their own language? My guess is that here is also where some kind of supervised learning comes into play as well as the implementation of some kind of heavy statistical analysis as mentioned in the previous paragraph. Without any knowledge of English, how could we know that “cortices” is the plural form of “cortex”? How could we know that “cortical” is the adjective form of “cortex”? How could we know that “cortazar” has nothing to do with the rest of the words above? How did we learn such relationships during our first encounters with the English -or any other- language for which we had no prior knowledge? As I said before, this relies in discovering patterns in the statistics of word occurrence, plus the presence of some kind of supervised learning (e.g. your teacher telling you that the plural of “cortex” is not “cortexs” but “cortices”, or that the plural of “mouse” isn’t “mouses” but “mice”).

Moreover, for the purpose of discovering the relationships among morphologically similar words clustered together we should also consider another way in which words or representations are formed in our minds (or brains, depending on what side of the fence you are watching from) which results from another core algorithm of reason. This one allows us to derive new concepts from existing ones by some sort of combination (see below). By virtue of this movement of reason, we are able to “pluralize” a concept (from “dog” we obtain “dogs”) even if we are not familiar with the “pluralizable” concept (if you read “kwyjibos” somewhere you would suspect that such word is the plural form of “kwyjibo”). Also, by virtue of this movement of reason we are able to “verbalize” concepts (“branch” becomes “to branch”) or “genitivize” concepts (“dominus” becomes “domini” in Latin). What is this algorithm of reason?

At some point during our early childhood years, we learned -I claim in an unsupervised way- the notion of plurality, that is, the notion of the many. For instance, once we learned that dog X and dog Y belong to a similar class or concept (that of “dog” without explicitly naming it so) we also learned that when perceived together dog X and dog Y make up the concept of “dogs”, without necessarily naming it so.

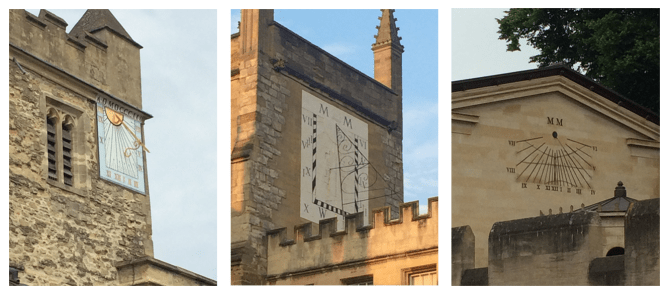

Here goes another example, look at the image below.

Do you know what is it? I don’t and I hope you neither, but they seem to be in every college in Oxford. Personally, I wouldn’t like to know their name nor their function because they allow me to understand how knowledge emerges in the mind. Anyway, now that you’ve seen Fig. 5, have a look at the next image.

This was taken in another college. Is the object shown in Fig 5. the same as in Fig. 6? Not the same, but similar. Why? Well, you’ll have to think about that. But at this point your reason has already extracted some similar features from both images and deemed both objects as instances of a single concept for which we don’t know yet its name nor its function. Now, look at the image below.

Is this new image another instance of the yet-to-be-known concept? Is it similar to Figs. 5 and 6? Surely they are, in the same way that dogs are not all the same. (There are breeds, you know.) They are similar enough to encompass them within a single concept, but different enough to deem them as different instances of it. Our minds already know that. If they, our minds, were brand new (almost a tabula rasa) and the objects shown in Figs. 5, 6 and 7 were among the first objects that we observed in the world, then by contemplating them together, as in Fig. 8, our reason would derive the notion of plurality in a natural and unsupervised fashion. (It’s out of the scope of this essay, but I also suspect that, contrary to what Kant suggested in his Critique of Pure Reason, somehow the concept of time is derived by reason early in our life.)

Later in life we learned notions like adjective, adverb, etc., which are all the forms in which concepts (and hence words) can be modified. These all are just concepts, that is, plurality, “adjectivity”, “adverbity”, etc. are concepts with the particularity that they modify concepts, and thus resulting in new concepts. (In mathematical terms, this reminds of the notion of “group”, but I’m not sure if they actually constitute one.) Therefore, when combining the concept of “plurality” with the concept of -say- “dog” reason produces a third concept, that of “dogs”. Let’s use the symbol æ to denote the function that goes from the cross product of the set of concepts to the -unidimensional- set of concepts. Thus, the example given a few lines above becomes:

æ(“plurality”, “dog”) = “dogs”

Finally, the question posed by Fig 4. which is to find the concept that mediates between the words “cortex” and “cortices” (or “cortical” and “cortex”) is the same as finding the concept that when applied the function æ on the concept “cortex” yields the concept “cortices”. In mathematical terms this implies applying the inverse of æ:

æ^-1(“cortex”, “cortices”) = x

Where x is the concept that we’re looking for. Naturally, the inverse is not always defined, and thus we won’t find a concept mediating “cortex” and “cortazar”.

What about the words shown in Fig. 3? Here the task is also to find the inverse of the function æ that reveals the concept that mediates between any two words in the cluster. For this purpose, as long as we don’t have a calculus of concepts (which we’ll probably never have) we would probably have to dive into a larger corpus comprising words in that arcane alphabet in order to find the patterns of word co-occurrence in which those words are present, and from there gain a better insight about their possible meaning and role. It could be that the three words refer to a concept which is named by one of them, and the other two are inflections of the word naming the concept. For instance, it could be that one of the words is the plural form, whereas the other is an inflection representing belonging in the same way that the word “domini” is the inflected form of “dominus” in Latin.

Coming back to AI, to the best of my knowledge there are no current techniques or algorithms that 1) cluster together input that is morphologically similar, 2) value prediction errors as much as prediction hits, 3) discover the relationships among elements comprising each cluster, and 4) based on that learn concepts and derive -almost autonomously- new ones. Coming back to my initial problem, the one that had me thinking about how word2vec discards word morphology and how much I wanted to avoid word stemming/lemmatizing in NLTK as I deemed it as an artificial solution, the ideas described above would help me to solve my very particular problem. Already half of the problem would be sorted out by having an algorithm that is able to cluster inputs based on their morphology. The other half would be solved by having an algorithm that somehow discovers the nature of the relationships -if any- of the words comprising each cluster. The icing on the cake would be to have yet another algorithm that maps all the words, for which there exist a conceptual relationship, to their canonical concept. For instance, the words “cortex”, “cortices”, and “cortical” should point to the concept of “cortex. Perhaps in this essay I have just set up my own future research and engineering agenda. Moreover, above I described a set of operations carried out over text input, but my guess is that the aforementioned set of operations occur with any type of input coming through the senses.

Above I spoke of “movements of reason”, and by that I mean its algorithms. Despite the teleological spirit surrounding the next claim, I’ve come to believe that the brain is the best thing that nature came up with in order to implement a very specific algorithm (or set of algorithms). It is our job as neuroscientists, philosophers and artificial intelligence researchers to unravel what is this algorithm.

In the First Working Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), the AudRecog module for auditory recognition seeks to resolve the differences between similar words in order to flush out the proper concept for any recognized word.

LikeLike